A long time ago in Cairo, with the pyramids in the distance, farm lands and the aqueduct. From the book "The Grand Street".

By Islam El shazly

The Grand Street of Historic Islamic Cairo, the heart of the once capital of the Fatimid Empire; as old as Cairo, it saw its fair share of kings and vagabonds. Walking through it amidst the ancient villas and the architectural marvels left behind by four dynasties, is like being transported into the world of the Prince of Persia – without all of the sand demons.

Taking a turn into one of the little alleys that spring out throughout the length of the street on a quiet day, stop for a moment and close your eyes, you can almost feel the ghosts of all the people who walked through here over the ages. There are shadows here. The time of the Fatimid also gave rise to their cousins, the Assassins. They lurked in the shadows.

But there is light here too, the whole length of the street is full of Masajid (Mosques), Madrasas (Schools), Bimaristans (Hospitals), Baths, and Sabeel/Kuttabs. Knowledge was available for all, and trade flourished here. It still does. Going inside one of the Kuttabs you can almost hear the walls still echoing the thousands of children who came to learn Quran.

The History

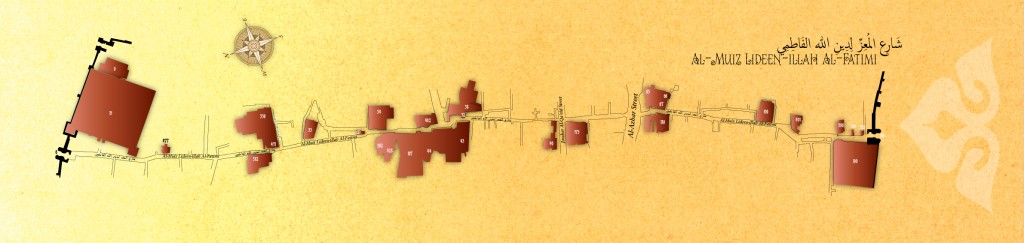

Called the Grand Street in by historians, Al-Mu’izz Street (Shariʻa al-Mu’izz li-Deen Illah) in Historic Islamic Cairo, Egypt, is probably the oldest street in Cairo, approximately one kilometer long, has the greatest concentration of medieval architectural treasures in the Islamic world according to a UN study. It is named for Al-Muʿizz li-Deen Illah, the fourth caliph of the Fatimid dynasty. It stretches from Bab Al-Futuh (The Gate of Conquests) in the north to Bab Zuwayla (The Gate of Zuwayla – A Moroccan tribe) in the south.

In the beginning it was restricted to the elite of society and members of the Fatimid royal family, whose villas and mansions lined the street on both sides. Slowly, it started transforming into a cultural and learning hub with a massive library. As time went by, wealthy merchants started replacing the original inhabitants.

Here is where Sultans paraded when they took over the regency, whether by inheritance or a coup, it didn’t matter. Sultans were made here.

Going through the full history of the street requires volumes; however, the Ministry of Culture published a very colourful detailed coffee table book about the street, its history, and its restoration, in 228 pages, complete with illustrations and pictures. The book is only available in Arabic.

North and South

Al-Mu’izz Street is commonly considered to consist of two sections, with the dividing line being Al-Azhar Street. The northern part extends from the Al-Hakim Mosque in the north to the Spice Market at Al-Azhar Street and includes Khan Al-Khalili market section, Al-Aqmar Mosque (one of the few extant Fatimid mosques), and the Qalawun complex, and several well preserved medieval mansions and palaces.

The southern part extends from the Ghuriya complex to the Bab Zuwayla and includes the magnificent Tent Market in the Gamaliya district.

The Walk

There are several ways to start exploring Al-Mu’izz Street: a) From the north end at Bab Al-Futuh all the way to Bab Zuwayla in the South, b) Starting at Bab Zuwayla in the South through to Bab Al-Futuh, c) Starting in the middle, at Khan Al khalili.

If you have time, the best way to do it is the third option, starting at Khan Al-Khalili, the midway point on the street, and split the itinerary over two days. That way you can enjoy a full day exploring the northern half and another day for exploring the southern half. The street is too rich to try and cram it all in a one day excursion.

Khan Al-Khalili to Bab Al-Fotouh

Walk through Midan Al-Hussein into Khan Al-Khalili, head down past Al-Fishawi, perhaps a cup of tea with mint or some Turkish coffee is in order. The pathway is called Sikket Al-Badistan, keep walking, it twists and turns a little but you walk until you get to a T-intersection, this would be Al-Mu’izz Street. Turn right (north) towards Bab Al-Fotouh.

For the next 500 metres or so, there are enough architectural marvels to make one’s head spin. On both sides of the street there are mansions, hospitals, schools, water fountains. For an instant they all look the same, but at close inspection, they are very different. Little tiny details here and there: a giant brass gate for this Madrasa and a massive carved hardwood door for the Masjid. You will not be disappointed.

The Sites

It’s mostly stores for the first few metres, but then the street opens up. The first site is on the east side of the street (the right side), is one of the oldest Ottoman sabeels still standing in Cairo, The Sabeel/Kuttab of Khassru Pasha, built circa 942 AH / 1535 CE, by Khassru Pasha, the Wali (governor) of Egypt on behalf of the Ottoman Empire. It stands next to the Funerary Complex of Salih Najm Al-Deen Ayyub.

Site No. 52. The Sabeel/Kuttab of Khassru Pasha (942 AH / 1535 CE). Details on the brasswork on one of the windows.

The Madrasa of Al-Salih Najm Al-Deen Ayyub, the first in Egypt to be built for all four Sunni schools of Islamic law followed the example of the Madrasa Al-Mustansiriyya in Baghdad (631 AH / 1233 CE ), was constructed under Al-Salih in 640-642 AH / 1242-44 CE. This was more than just a scholarly centre, here the four chief religious justices, or Qadis, heard cases referred to them from lower courts. They formed the supreme judicial tribune of the state. This was the centre of the town, the courthouse square of Cairo.

Site No. 38. Funerary Complex of Salih Najm al Din Ayyub (648 AH / 1250 CE). Inside the dome with some gold inlays on the pillars.

The mausoleum, the first in Egypt to be attached to a madrasa, was built by Al-Salih’s wife Shajar Al-Durr “String of Pearls” in 648 AH / 1250 CE.

Across from Al-Madrasa Al-Salihiya lies the Sultan Al-Mansour Qalawun Complex. It was built for the Sultan by Amir ‘Alam Al-Deen Sanjar Al-Shuja’i in 682-685 AH / 1284-5 CE and consisted of the founder’s mausoleum, madrasa, and a maristan (hospital). The hospital was the most sophisticated medical centre of its time, with separate wards for fevers, eye diseases, surgery, dysentery, and mental illness.

Site No. 43. The Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun Complex (682-685 AH / 1284-5 CE). The Mihrab (prayer niche) and Minbar (pulpit).

The complex was built over what used to be the Western Palace, the residence of Sett Al-Mulk, the daughter of the Fatimid Caliph Al-‘Aziz Billah Al-Fatimi. Men’s bathhouse and caravanserai were later attached to the bimaristan, they are no longer standing.

Located opposite the Complex of Al-Nasser ibn Qalawun stands the Sabeel of Mohammad Ali – Nahasseen “Cppersmiths“, it was built by Mohammad Ali Pasha in memory of his son Ismail Pasha who died in 1822 CE. After it’s restoration it was transformed into the new state-of-the-art Egyptian Textiles Museum. The displays start at the Pharaonic period through the Islamic period. On display is part of the Kiswah (Cover) for the Ka’aba; that was commissioned in the 1940’s by King Farouk. The museum is open from 09:00am-08:00pm (tickets booth closed at 07:30pm) and the tickets are EGP2.00 for Egyptian adults, EGP1.00 for students, EGP20.00 for foreign adults, and EGP10.00 for foreign students.

Construction of the Madrasa of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun was begun under Sultan Al-‘Adil Katbugha who ruled briefly (1295-6 CE) after Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad’s first reign (1294-5 CE). When Sultan Al-Nasir took back the throne, he bought the yet unfinished madrasa and completed its construction. Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad’s second reign lasted from 1298 to 1303 CE.

The portal, a remarkable piece of Gothic marble work, is a trophy seized from a church in Acre, the last Crusader stronghold in Palestine. It was brought to Cairo at the behest of Sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil ibn Qalawun, who conquered Acre in 1291 CE, and was assimilated into the facade of the madrasa by Al-‘Adil Katbugha. Source the link works only on IE!

Built by the founder of the Burji or Circassian Mameluke dynasty, Al-Malik Al-Zahir Sayf Al-Deen Barquq Al-Cherkesi, the Madrasa and Khanqah of Sultan Barquq was built between 786 and 788 AH (1384-1386 CE). The Complex consists of a madrasa, a khanqah – a house/convent for Sufis – and a mausoleum, and is attached to the two Qalawun complexes.

Site No. 187. Sultan Al-Zahir Barquq Funerary Complex (786-788 AH / 1384-1386 CE). Embellishments and Islamic designs on the ceiling.

The architect Shihab Al-Deen Ahmad ibn Muhammad Al-Tuluni, who belonged to a family of court architects and surveyors, was in charge of part of the construction. The name of Jarkas al Khalili, the master of Barquq’s horse and the founder of the famous Khan Al-Khalili, appears in the inauguration inscription on the facade and in the courtyard. Source.

Standing to the West of al-Nahasseen (coppersmiths) Street is Al-Madrasa Al-Kamiliya, the school, built in 622 AH / 1225 CE by Sultan Al-Malik Al-Kamil Naser Al-Deen Abu Al-Ma’ali Muhammed, the fifth Sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty, originally consisted of two buildings the remaining of which is the western building.

Site No. 428. Al-Kamileya School (622 AH / 1225 CE). The remaining Iwan after restoration, from the book "The Grand Street".

This was the second school to be dedicated to teaching Hadith, the first being that of established by Al-Adel Nurredin Mahmoud Zinki in Damascus, Syria.

Site No. 562. The Hammam (bath) of Sultan Al-Ashraf Inal (861 AH / 1456 CE). From the book "The Grand Street".

Hammam Inal stands on Al-Mu’izz Street and dates back to 1456 CE. The front faces Al-Mu’izz Street and the building is designed so as to prevent pedestrians from watching what takes place inside. The reception hall is square with a wooden roof and with a 28-window skylight. It was commissioned by Sultan Al-Ashraf Sayf Al-Deen Inal Al-‘Ala’i.

The Palace of Amir Bashtak was built by Amir Sayf Al-Deen Bashtak Al-Nasiri, Al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun’s son-in-law, in 1334-39 CE on a portion of the site of the Fatimid Eastern Palace (al-Qasr al-Sharqi).

Site No. 34. Amir Bashtak Palace (735-740 AH / 1334-1339 CE). The inside of the Palace, from the book "The Grand Street".

It remains nearly complete in its original form, with two stories, qa’a “hall“, a small courtyard, and integrated stables which have a special gate opening onto a side street.

The long facade was endowed with many windows opening onto the busiest street in medieval Cairo.

Site No. 21. The Katkhuda Sabeel/Kuttab (1157 AH / 1744 CE). The sabeel and the some of the crafts on display for sale inside.

The Sabeel/Kuttab of ‘Abd Al-Rahman Katkhuda was built by the famous Prince ‘Abd Al-Rahman Katkhuda in 1175 AH / 1744 CE. It was built to provide water to passersby and on the top floor was a kuttab “school” dedicated to teaching Muslim orphans. Its south side faces Prince Bashtak’s Palace. Katkhuda was a Mameluke Amir and leader of the Egyptian Janissaries. It is now used to house a collection of handmade crafts for sale by Al-Foustat Center.

Jamie’ “Mosque” Al-Aqmar was commissioned by the 10th Fatimid Caliph Al-Amir bi’Ahkam Allah and its building was overseen his vizier Al-Ma’mun Al-Bata’ihi. It was completed in 1125 CE. The brick minaret, along with restorations including the mihrab and minbar, was introduced by the Mameluke Amir Yalbugha Al-Salimi in 1397 CE.

Site No. 33. Jamie' "Mosque" Al-Aqmar (519 AH / 1125 CE). No mausoleum inside means if you are a muslim you can pray in it.

Though rising ground levels make the mosque appear at street level, it was originally built above a row of shops which are now buried. These shops were “waqf” or endowment for the mosque which would have provided it with a tax-exempt income.

The Mustafa Jaafar Mansion sits at the head of Al-Darb Al-Asfar alleyway which branches off Al-Mu’izz Street. To its south-east lies Al-Khazarati Mansion which stands in the vicinity of Al-Suhaymi Mansion. It was built in 1125 AH / 1713 CE by Mustafa Jaafar Al-Silihdar, a major 18th century coffee trader.

The three mansions can be accessed through Al-Suhaymi Mansion (Site No. 339) that was built in 1058 AH / 1648 CE. The mansions have been undergoing major restoration and renovation to bring back their past glories. Now they play host to folk and cultural events in the evenings. Entry fees are EGP 3.00 for Egyptians and EGP 30.00 for foreigners.

One of the most magnificent mosques, the Masjid, Sabeel, and Kuttab of Al-Silihdar was built by Amir Suleiman Agha Al-Silihdar the Master of Arms during Mohammad Ali Pasha the Great’s rule.

Site No. 382. Al-Silihdar Complex (mosque, caravanserai, Sabeel, and school) (1355 AH / 1837 CE). The minaret and the sabeel, from the book "The Grand Street".

Al-Silihdar Complex has three courtyards to which are attached a caravanserai and a school. The mosque’s wooden arcades are a mixture of traditional oriental elements and western elements, brought from Europe to Istanbul in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Tucked away between some shops is Site No. 477. Zawyat Abul-Kheir Al-Kelibati, it stands on Al-Kelibati Street off Al-Mu’izz Street in historical Cairo. It was built under the Fatimid Caliph Abu Al-Hasan Ali Al-Ẓahir Li-I’zaz Deen Allah who ruled from 411 to 427 AH (1021-1036 CE).

The Jewel of the north side of Al-Mui’zz Street is the Mosque of Al-Hakim. Construction of the mosque was begun by the Fatimid Caliph al-‘Aziz in 990 CE and finished by his son, the sixth Fatimid caliph, Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah and his overseer Abu Muhammad Al-Hafiz ‘Abd Al-Ghani ibn Sa’id Al-Misri in 1013 CE.

Site No. 15. Al-Hakim Mosque (380-403 AH / 990-1012 CE). Open to the sky, from the book "The Grand Street".

The Mosque was originally constructed outside Jawhar’s city walls, and was later included within the city when Cairo was expanded during the reign of Al-Mustansir bi-llah in 480 AH / 1087 CE, his Vizier Badr Al-Deen Al-Jamali expanded the city’s boundaries from the north and the south. In the north side he made the new city wall follow the contour of Al-Hakim’s Mosque.

As with Al-Aqmar Mosque, there are no mausoleums inside, which mean if you are a Muslim and you need to pray during your walk you can pray in either of the two mosques.

By the time Al-Mustansir bi-llah came to power in 480 AH / 1087 CE Cairo had grown out of its original sun-dried brick wall of Jawhar. At the time one of the most powerful Viziers in Fatimid history, Badr Al-Deen Al-Jamali, moved to refortify the city and build a new wall made of stone to compensate for the city’s growth and to better protect it against rising threats from the east.

Site No. 6. Bab Al-Futuh (480 AH / 1087 CE). The Gate of Conquests, from the book "The Grand Street".

Bab Al-Futuh “The Gate of Conquests” built in 1087 CE was part of this rebuilding campaign which included two other gates: Bab Al-Nasr “Gate of Victory” and Bab Zuwayla. Bab Al-Futuh and Bab Zuwayla mark the northern and southern limits respectively of the Fatimid city.

As the name entails, Bab Al-Futuh was used by armies leaving for battle, While Bab Al-Nasr, about 150 metres to the east, would be the entry point for their victorious return.

Once you exit this gate, you have officially left the northern boundaries of the original Cairo. There are other expansions and restorations that were carried out through the years. During the work on Al-Azhar Park a wall was unearthed that was part of the expansion by Salah Al-Deen, by his time the Cairo had grown significantly, and could no longer be contained within the old walls.

Enjoy your walk.

Tags: Al-Mu'izz, AlMuizz, Ayuub, Barquq, Bimaristan, Cairo, Caravanserai, Conquests, Fatimid, Futuh, Ghuriya, Hospital, Islamic, Janissaries, Khanqah, Kuttab, Madrasa, Mameluke, Mamluk, Mansion, Maristan, Ottoman, Pearls Textiles, Qalawun, Sabeel, Sabil, Suhaymi, Sultan, Vizier, Vizir, Zuwaila

Trackbacks for this post