Commodity Trading

All my UML examples so far have been in the insurance and healthcare space. In this post, I attempt to apply UML to a topic which is in the financial service space – the commodity markets.

Commodity markets have become a hot button issue in recent times. Speculation on the commodity markets is being blamed for the meteoric rise (and subsequent fall) in the price of oil. While I am not in a position to support or refute this stand, I am in a position to illustrate, using UML, how commodity markets are setup to operate.

Let us start with some definitions.

Definitions

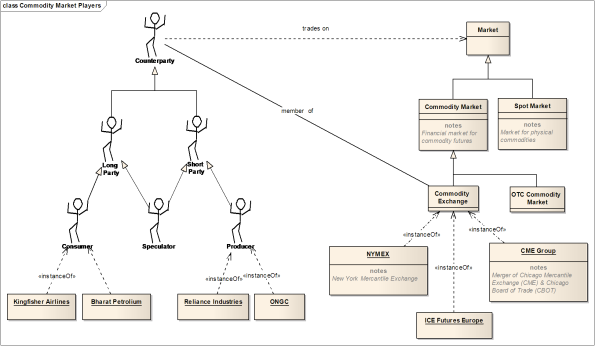

The class diagram below depicts the various parties that participate in commodity trading.

Note that some these classes (the ones that model physical actors) are not notated by the usual box notation. Instead the notation looks like (but is not) that of actors in UML. I have associated an alternate image with these classes. This is allowed by UML 2.0 and is supported by any respectable UML tool.

The reason I chose to use this “dancing men” notation is that these classes are very similar to actors, i.e. they encapsulate the attributes and behaviours of actors.

This model, though sound, is far from complete, but is sufficient to illustrate the workings of the commodity market.

Fundamentally, commodity markets are financial futures markets that are used by producers and consumers of various commodities to hedge against the effect of fluctuating prices of those commodities in the spot market.

As opposed to commodity markets, a spot market is the notional marketplace in which physical commodities are bought and sold every day. Spot prices (i.e. prices in the spot market) tend to take their cue from prices in the commodity markets. In other words, commodity markets act as a price discovery mechanism for the spot market. In reality, the spot market is nothing but the network of buyer and supplier relationships that all businesses setup and nurture to keep their lifeblood flowing.

Having said that, I should clarify that commodity markets are set up to deal in physical commodities also (as opposed to being pure-play financial markets), i.e. a buyer can choose to take delivery of a physical commodity and a seller can choose to make delivery. The ground reality is that over 90% of trades in commodity markets never proceed to physical delivery and are closed financially. Hence you will not go wrong if you think of commodity markets as pure-play financial marketplaces.

In addition to producers and consumers, speculators play a role in providing liquidity in the commodity markets (i.e. they ensure there are enough buyers to match the supply and enough sellers to meet the demand). Speculators are motivated by a desire to capitalize on short-term price fluctuations.

All these parties trade commodity futures on a commodity exchange, i.e. they are counterparties in commodity futures trades – one buys (i.e. is the long party) and the other sells(i.e. is the short party).

A commodity exchange is a market place where commodity futures are traded. This is a physical realization of the concept of a commodity market. An exchange provides the necessary infrastructure (physical and / or computerized) for buyers and sellers to find each other and strike trades.

It is also possible to trade without using an exchange. Such trades are called Over the Counter trades (OTC trades) and are essentially customized contracts struck directly between two parties without the intervention of an exchange. We will not concern ourselves with OTC trades in this post.

So, what are commodity futures?

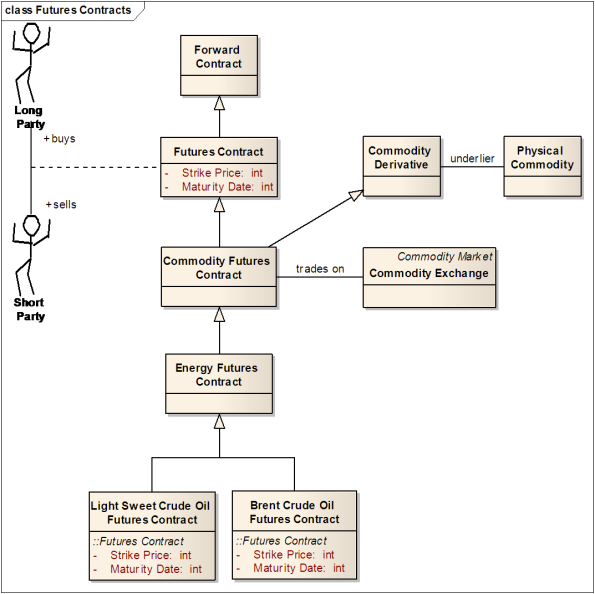

A commodity futures is a standardized, exchange-traded contract to buy / sell a specified commodity at a specified price (refered to as the strike price) on a specified date in the future (refered to as the maturity date).

For example, one Light Sweet Crude Oil Dec 2008 Futures contract on NYMEX is defined to be 1000 barrels of Light Sweet Crude Oil with certain technical specifications to be delivered in Dec 2008.

Since a commodity futures contract derives its value from the value of the underlying commodity, it is considered to be a derivative instrument with the commodity being its underlier.

Is there any such thing as a non-standardized, non-exchange traded futures contract? Yes, and that is called a forward contract. Forward contracts are customized OTC trades which bet on the future price of assets. We are not concerned with forward contracts in this post and I mention them just for completness of these definitions.

Armed with these definitions, we can now proceed to examine how the commodity market operates from the perspective of a producer of a commodity, say crude oil.

The Producer’s Perspective

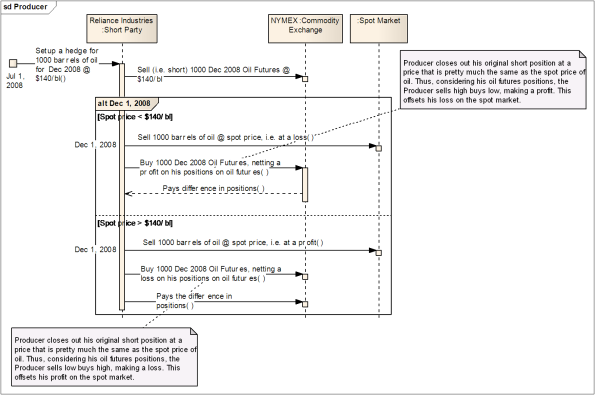

The sequence starts in July 2008, when crude oil price is around $140/barrel.

A producer of crude oil (say Reliance Industries) is worried that due to legislative action by the US government, crude may drop significantly lower by Dec 2008. The producer is desirous of locking in the price of oil in Dec 2008 at current levels.

The producer offers to sell a certain number of Oil Futures contracts (say 1000 futures) maturing in Dec 2008 @ $140/bl, i.e. he takes a short position on oil futures (the diagram depicts the more generic Short Party instead of a Producer).

A counterparty (i.e. a Long Party, who can be either a consumer or a speculator) accepts this offer, i.e. takes a long position on oil futures. This step is not shown in the diagram as it does not add value to the main story line.

Come Dec 2008, the producer takes a compensating position on Dec 2008 Oil Futures, i.e. he buys Dec 2008 Oil Futures in Dec (yes, he buys futures which are pretty close to becoming the “present”). This is informally refered to as closing out an original position.

What is the point in doing this?

Consider the two possibilities of movement of spot oil price in Dec:

Spot price of oil in the physical market drops below $140/bl. In this case, the producer will have to sell oil at a loss in the physical market. On the other hand, he stands to gain on his short position on oil futures which he struck way back in Jul 2008! This gain on his futures position offsets his loss in the physical commodity and the net effect is the producer gets $140/bl.

How does the producer gain on his short position on oil futures?

The key to understanding this is to note that in Dec 2008, the price of Dec 2008 Oil Futures will pretty much be the same as spot price of oil.

Hence, all that the producer has to do now is to buy the same number of Dec 2008 Oil Futures as he originally sold. Thus, the producer has sold futures high and is now buying futures low thus gaining, in hard cash, the difference between his original oil futures contract strike price and the current oil futures contract price (which is pretty much the same as the spot price in Dec).

Consider the other possibility: Spot price of oil in the physical market goes above $140/bl. In this case, the producer can sell his oil at a hefty profit in the physical market, but he stand to loss on his short position on oil futures which he struck way back in Jul 2008! Thus the gain on sale of physical oil is offset by his loss in his commodity futures position and the net effect is the producer gets $140/bl.

Thus, either way, the producer gets $140/bl, i.e. he has locked in the price of oil in Dec 2008 at $140/bl irrespective of which way the spot price of oil fluctuates. This is called hedging.

Note that the two fragments of the alt combined fragement on the sequence diagram are identical, i.e. irrespectice of which way oil price moves, come Dec 2008, the producer takes that same actions! What changes is the notion of profit and loss (very important notions these) depending on which way the spot price of oil moves.

Finally cosider what happens if the producer does not close out his original position? He has to make physical delivery of oil, of course!

The Consumer’s Perspective

In the case of a consumer of a commodity, the whole scenario is an inversion of the producer scenario.

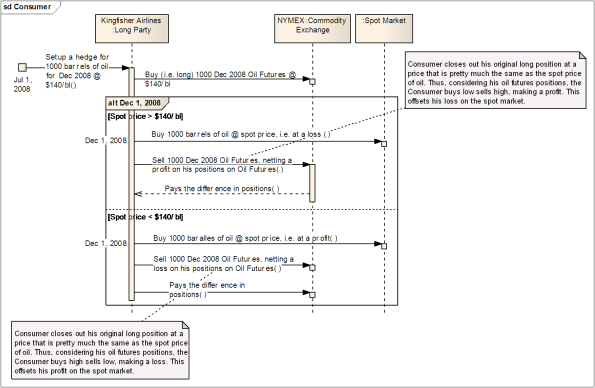

Once again, the sequence starts in July 2008, when crude oil price is around $140/barrel.

A consumer of crude oil (say Kingfisher Airlines – Mr. Mallya has to worry about aircraft fuel as well as fuel for his F1 race cars!) is worried that crude may rise significantly higher by Dec 2008. The consumer is desirous of locking in the price of oil in Dec 2008 at current levels.

The consumer offers to buy a certain number of Oil Futures contracts (say 1000 futures) maturing in Dec 2008 @ $140/bl, i.e. he takes a long position on oil futures (the diagram depicts the more generic Long Party instead of a Consumer).

A counterparty (i.e. a Short Party, who can be either a producer or a speculator) accepts this offer, i.e. takes a short position on oil futures. This step is not shown in the diagram as it does not add value to the main story line.

Come Dec 2008, the consumer closes out his original position, i.e. he sells Dec 2008 Oil Futures in Dec (yes, he sells Futures which are pretty close to becoming the “present”).

What is the point in doing this?

Consider the two possibilities of movement of spot oil price in Dec:

Spot price of oil in the physical market goes above $140/bl. In this case, the consumer has to buy oil at a potentially significant loss in the physical market, but he stand to gain on his long position on oil futures contract which he struck way back in Jul 2008! Thus the loss on sale of physical oil is offset by his gain in his commodity futures position and the net effect is the consumer gets $140/bl.

How does the consumer gain on his long position on oil futures?

The key to understanding this is to note (as already indicated above) that in Dec 2008, the price of Dec 2008 Oil Futures will pretty much be the same as spot price of oil.

Hence, all that the consumer has to do now is to sell the same number of Dec 2008 Oil Futures as he originally bought. Thus, the consumer has bought futures low and is now selling futures high thus gaining, in hard cash, the differece between his original oil futures contract strike price and the current spot price.

Consider the other possibility: Spot price of oil in the physical market falls below $140/bl. In this case, the consumer will buy oil at a profit in the physical market. On the other hand, he stands to loose on his long position on oil futures contracts which he struck way back in Jul 2008! His gain in the physical commodity is offset by his loss on his futures position and the net effect is the consumer gets $140/bl.

Thus, either way, the consumer gets $140/bl, i.e. he has locked in the price of oil in Dec 2008 at $140/bl irrespective of which way the spot price of oil fluctuates.

Once again, what happens if the consumer does not close out his original position? He has to take physical delivery of oil!

The Speculator’s Perspective

What is the speculator’s motivation in this?

Note that in the scenarios depicted above, whenever the producer / consumer looses on the futures market, the counterparty (which will most likely be a speculator) gains. It is this possibility of gain that keeps the speculators going. This gain depends on how actual spot price of oil moves, i.e. the speculator is betting on the uncertainty of which way the spot price of oil will move; this is the definition of speculation – betting on uncertainty.