The good thing about being Proprietor, Publisher, and Principal Reporter on this site, is that when you rush in from an afternoon fighting the undergrowth and shout – Hold the front page! . . . there’s no argument. Everything stops. Those hot pixels about your third excursion to the southern Corbières? Spiked – for the moment.

But I can’t start shouting – ‘Read All About It ! Dolmen Found at Montbrun!’ – not yet. Not until I have informed the C.N.R.S. and written to S.E.S.A. and had my fingerprints taken and sworn on the Bible/sung the Marseillaise. It could, after all, just be a pile of old stones.

There is not much to be seen in the photo above – even after an hour of ‘gardening’. So what is there to go on? No discernable orthostats – nothing upright at all. No headstone and no capstone.

The impetus to go looking for this megalithic site was prompted by the findings in the previous Post: that many (not all) stone structures are located near old-established boundaries. And further: that neolithic clan territories may have formed the shape of modern France. From memory, and with a bit of research, I was able to show a score of dolmens and menhirs that followed this pattern. One of them was in fact close-by our nearest village, Montbrun-des-Corbières.

We’ve walked this ridge many times and I’ve looked here and on the neighbouring hillside above Lézignan for another ‘Pierre Droite’. Not having found that one – I assumed that the good people of the region had smashed them both.

[Note: our market-town was once known as Lézignan-les-Réligieuses ( Guerres de Religions). Earlier it was suspected of being another Cathar hot-bed. I, for one, am heartily sick of ‘the Caffars’. Any mention of them brings out my ‘inner de Monfort’. Mawkish tourists gawking at a minor religious train-crash makes me want to mount another crusade . . .]

So with religious fever running high for centuries throughout the region, it would be ‘a miracle’ if any pagan monument remained standing. Wherever I see a ‘Pierre Plantée’ or ‘Peyro Dreto’ on the map I will dutifully waste an afternoon in order to be able to state with reasonable authority – that there’s nothing left to be seen.

But I had not actually searched this part of the ridge. If I accuse other megalithic guide-book writers of laxity I had better be careful – and pull myself away from the computer, head out into the gale and come back with nothing as usual but the scratches.

Except this time I would do it properly – with Google Earth GPS waymarks an’ all. I would cover the whole area: every clump of trees, every thicket of thorns. And this is what I found:

These are the two major stones of the group – neither are even one meter long or wide. So why even start clearing the undergrowth? Because two of the three criteria had been met: first – these stones have ‘form’, that is: a history and a placement and a local occitan name. Second – they have an orientation: precisely East-West. This site has other attributes which are indicative if not definitive: it is three metres long (about average for a ‘dolmen simple‘. And it is one meter wide. There are no other stones in the vicinity – it is not part of a collapsed wall enclosure, or old sheep-pen.

So now we need the experts – and if it turns out to be nothing significant, then at least I tried.

[Another note: how ‘dolmens’ and ‘pierres droites’ can get confused is for the next post.]

[And one note more: I have now notified the Vice-President of SESA, Michel Prun, of my ‘discovery’. For the last three years he has been a great help in the library. All the coordinates and photos have been sent to SESA, and the archaeologist-in-charge Guy Rancoule, has been notified. SESA’s once youngest, and now oldest member – Regis Aymé – has volunteered to visit the site to give his opinion. I could still end up looking like a fool. Or I could have ‘unearthed’ my first dolmen.]

All the rain that never fell this summer is falling now and will continue to fall for days yet.

Which gives me time and excuse enough to work up my latest observations into a Grand Theory. In the course of the last few weeks I have been trying to make sense of the scant information about the dolmens of ‘les causses de Siran’ that has filtered down through the decades, and thus locate and identify them. One small key was a brief mention of the Peyro-Rousso dolmen by Jean Miquel de Barroubio in his 1896 ‘Essai sur l’arrondissement de St. Pons’. The dolmen, he says, is both ‘un rendezvous de chasseurs’ and ‘une borne entre les communes de Siran et La Livinière’.

Earlier this year I had noted that the two dolmens at Fournes, and the menhir, were also located at a boundary: that between Siran and Cesseras. Yesterday it occurred to me that these may not be solitary examples, accidents or exceptions: there might be others.

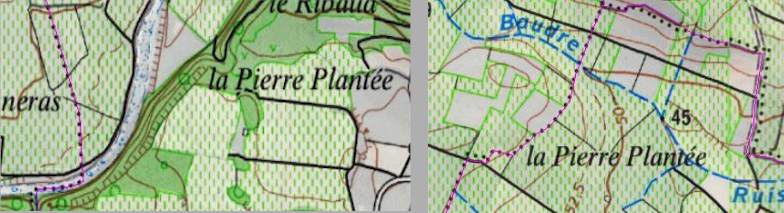

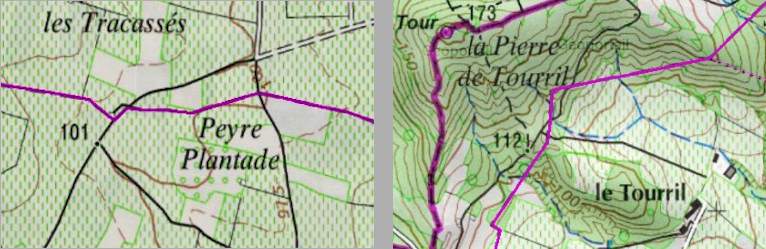

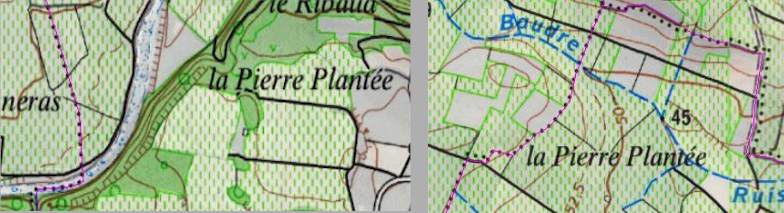

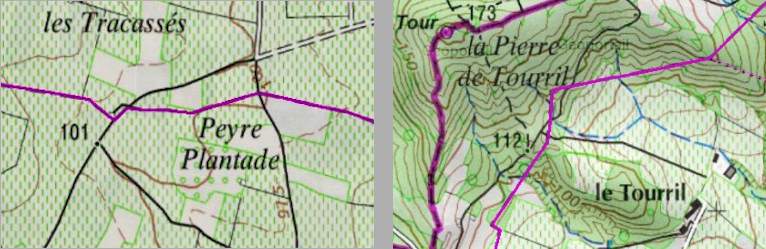

There were indeed. To economise on space I have randomly paired the following screen-captures of megaliths in the area. The purple line appears when you add the ‘Unités Administratives > Limites Administratives’ layer on the IGN GeoPortail.fr site.

There are twenty so far: the last example – the two menhirs at Tournissan – is the most graphic.

Above : Agel and Ventenac – Below : Arques and Talairan

Above : Azille and Tourril – Below : Balsabé (or Cigalière) and Jappeloup

Above: in the top left corner the dolmen of les Lauzes couvertes, or Liquieres, near Cébazan – and the two Villeneuve dolmens.

Below : the vanished standing-stones above Conilhac and Montbrun.

Above: Pépieux and Monze – Below : Laroque-de-Fa and Talairan

Above: one of the Massac dolmens, and (unmarked) the dolmen de la Roudounière – see Page, left.

Below: Trassanel and Olonzac

Below: two views of the menhir at Malves

And below are the last two: left – the higher of the two menhirs at Tournissan and right – the stone by the roadside.

Here they are seen together : there is no mistaking which direction the boundary line is following –

And here is a late addition: I should have thought earlier of the Grand Menhir de Counozouls. It is 500 m. from the boundary between the communes of Counozouls and Roquefort-de-Sault, and 200 m. from the ‘ancien chemin‘ that linked the two villages. At 8.9 metres tall, and weighing 50 tons, it is the biggest in southern France, and one of the largest in Europe.

My theory is stuck at the ‘Chicken or Egg’ stage (for foreign readers, this means “Which came first – the chicken or the egg?” It’s a common, if false dichotomy): were megaliths just useful and durable objects in a landscape, allowing communal boundaries to be easily drawn? Or were communes the extension, into a more modern world, of Neolithic tribal or clan territories? And if dolmens were sited so close to the borders of a neighbouring group – what implications does that have for our understanding of the functions and rituals that surround the burial-place? Were menhirs placed there as a warning or a welcoming sign?

Of course, what I have not shown are all the megaliths that are located far from any boundary-line. I don’t yet know which are the greater in number. Nor whether it is worth pursuing : perhaps it’s all random – perhaps all can be explained by ley-line energies.

Before Quid.fr suddenly went offline at the end of March this year, I had, fortunately, saved exactly what this ‘Encyclopedia Gallica’ had reported on the prehistory of the commune of La Livinière :

# Dolmens de Combe-Marie, Calamiac, Combe-Violon, Combegrosse, Les Meulières, Fonsorgues, Pierre Rousse, Caussérel, Saussenac, Castel Bouqui.

# Alignement mégalithique à Saussenac.

# Habitat chalcolithique au nord-est de La Livinière.

# Traces de village néolithique à Parignoles.

Unfortunately there was no means of quizzing Quid about its sources – and now it is too late. Take that first entry : of the 10 dolmens cited, I have found only 3. The rest seem to have no parentage, and no further references. But they will haunt me for a good while yet – until I either track them down, or eliminate them as duplicates or confusions.

However – I may have found what is referred to in the second entry. Given the modest dimensions of our little neolithic sepulchres, this ‘Alignement mégalithique’ was never likely to win a prize in the All-France Henge Competition.

But it was intriguing and (increasingly) impressive, when I stumbled across it earlier this year while looking for the Combe Lignières dolmen :

It is an utterly enigmatic construction, 12 metres long and about 1 metre wide.

I would hazard a quess that it was first noted by Jean Miquel de Barroubio in the 1890’s. Erik Trinkhaus & Pat Shipman’s ‘The Neandertals’ (Pimlico 1993) sheds some light on these early days of archaeology and anthropology. Their chapter on ‘L’Affaire Moulin Quignon‘ illustrates the rush to satisfy this era’s (mid 19th. c.) appetite for prehistoric artifacts and bones.

The early amateur-prehistorian, Boucher de Perthes, claimed to have located a hominid jawbone in a quarry near Abbeville in Picardy. He had been finding ‘bi-face‘ flint tools in the area for 30 years – and desperately needed fossilized bones to go with this early human industry. Local workmen duly presented him with this example, supposedly accompanied by a flint axe, both from a layer dated to 300,000 BCE. Other French experts backed him, while German and English experts were skeptical. An international commission was called in 1863, and it became a ’cause célèbre’. The English were permitted to study a tooth from the jawbone – and found it to be not fossilized at all, and probably neolithic. The French refused to countenence these findings, and pronounced in favour of Boucher. Jacques Boucher died in 1868, still proclaiming it to be authentic. Within 30 years the French had quietly dropped their support, without ever formally declaring it to have been a fake.

Trinkhaus & Shipman stress the following point: ‘ At Moulin Quignon, there was probably little intention to foil the progress of science. Almost certainly, the motivation was a transparently simple one: if Boucher de Perthes would pay good money for hand-axes, and promised even better bonuses for bones, why shouldn’t the workmen indulge him, and enrich themselves? What could be the harm?’

Well, the harm could be considerable. To the reputation of this early scientist in particular, to the reputations of subsequent amateur archaeologists in general, and to the methods employed by other ‘gentlemen-scientists’.

Trinkhaus & Shipman stress that this ‘find’ of Boucher’s was not an isolated incident: ‘As early as 1859, rumours and scurrilous stories were circulating that Boucher was being fooled by modern, counterfeited stone tools. Because of the near-universal practice of paying workmen to excavate and rewarding them for good finds, the door was wide open to fakery. Indeed, the Abbeville area was notorious for it, perhaps because of Boucher’s unbridled enthusiasm.’

One of the probably apocryphal stories is as follows: ‘While walking through the streets of Abbeville, a gentleman passed a peasant sitting on his doorstep, diligently chipping stone. When asked what he was doing, he replied, “I am making Celtic axes for Monsieur Boucher.”

I have cited this at length because it goes some way to explaining how our own local ‘gentlemen-prehistorians’ managed to amass such an extensive catalogue of sites – in Jean Miquel de Barroubio’s case, the entire length of the Minervois Hills from Carcassonne to St. Pons. As I have discovered, it takes many weeks of visits to cover just a few sections of ‘causses’. His list of prehistoric sites was almost certainly compiled with the help of scores of ‘informants’ : shepherds and herdsmen, farmers and forestrymen, hunters and poachers . . . Word had undoubtedly gone out, that a wealthy landowner and collector was seeking suitable sites and artifacts. This, I am fairly sure, was how the original lists were made, with all their confusions and duplications and variations, over names and locations. And, possibly, how and why so many dolmens were pulled apart to get at the grave-goods within.

Capstones weighing many tonnes are not lifted clear by a pair of grave-robbers. A beam of sufficient length and strength would need a small band of men to carry it the many kilometres on site. Larger capstones would require a strong draught-horse, or a couple of oxen, complete with harness and thick rope or chains. This amount of equipment and manpower must have been paid for somehow.

Why prehistory had suddenly, in the mid-19th century, become worth spending time and money on – had in fact become a Europe-wide fascination during this epoch – involves Darwin and the rise of Prussia. But all that must wait for another post.

For more photos & information about the Saussenac Stone Alignment – see under Pages >Menhirs.

We’re still up on Le Causse de Siran – and could be here for quite a while yet . . .

It’s a big, heart-shaped expanse of featureless garrigue, ribbed with little gullies and sudden ravines – and at its widest it is three kilometers across. If the Peyro-Rousso dolmen marks its western border with the commune of La Livinière, then its eastern limit is marked by the two Fournes dolmens – and this standing stone. The boundary-line between Siran and Minerve to the east runs right through it.

It’s not very big or impressive – which may explain why it has gone unremarked. The only place it appears is on Bruno Marc’s list of menhirs of Herault – where it is described as 1m. 35 long (about right) – but ‘couché’ : fallen over.

However – this stone does not look like it has recently been resurrected (extensive evidence of weathering and more importantly, lichens) : so one wonders where Marc got his information from. I suspect that part of his list for the Aude and Herault is based on Sicard’s 1929 Inventory.

Menhirs cause trouble. They may not mean to – but they do. Some are magnificent – and somewhat manly. Others are more modest. Some are carved and others are just lumps of rock. This one is on a border line and has an ‘orientation’ of North/South, while others seem to ‘point’ in random directions and are in the middle of nowhere. Some have neolithic artifacts around their bases – others are documented as mediaeval constructions.

And then there are the theories that would have these stones as geo-astrologic artifacts : coordinates for mapping the heavens or conduits for ley-line energies.

[Note: In the interests of balance and fairness – here is a link to a site that takes all that stuff very seriously, and a stage further. It’s a home-grown site that maps our region into a veritable spiders-web of energies. So you can all go out and put his exhaustive theories to the test. Please report back here the moment you feel more centred, or spiritual – or silly.]

I sometimes wish I had not stumbled across this one : there is just too little – or too much – to say on the matter of Lone Stones.

There is more (basic) information and a few more photos on the Fournes menhir Page – now to the left, on the new-look site. GPS coordinates will be available through SESA in Carcassonne, or from me.

I am re-writing this post in the light of a key piece of information that I had overlooked : a brief description of a dolmen on Le causse de Siran in a 1896 Essai that tallies with the dolmen I found.

There are anything from 8 to 19 dolmens on ‘ les causses de Siran ‘ – according to the (deliberately?) vague accounts of the earliest searchers: Jean Miquel de Barroubio in 1896, and Paul Cazalis de Fondouce, in 1905. Others came in subsequent decades – but each researcher merely repeated the findings of the first two, without adding any further information.

In 1946 Jean Arnal claimed to have found 22 dolmens ‘sur les causses de St. Julien ‘ – by which he meant the Causses of La Liviniére and Siran. Half of them were neither named nor given precise locations. In 1971 and ’72 Paul Ambert undertook a survey of the area, and stated that he had found 18 of them. I detected a note of his exasperation (possibly disbelief) in Docteur Arnal’s claim to have found so many – particularly the dolmen at St. Marcel. Ambert was not only unable to find this dolmen – he could not find any place named St. Marcel anywhere on the map, either.

There is a recurrent pattern of behaviour amongst archaeologists of that early era – they are ‘economical with the truth’. They hold back information, they obfuscate – they lie. It may have been that back then in Jean Miquel’s time, the common practice was to employ crude men and methods to extract the grave-goods that they so valued for their collections. Or that they wanted to keep their secret locations to themselves.

Nowadays, the problem is guide-book writers whose aim is to sell books and therapy courses. Accuracy and precision have again been abandonned. Bruno Marc’s ‘ megalithic portal to the south of France ‘ covers a large area, but accuracy and detail are sometimes lost along the way. There is a list of prehistoric sites for the Herault and the Aude that is out-of-date at best (though it claims to have been updated in 2009), and frequently fictional at worst. By fiction I mean – the writer has not visited some of these sites, has no photos of the dolmens, has taken no measurements nor orientation. The key test, with all these scattered, sad, semi-derelict sepulchres is – what is the geographic location for the megalith? And where is the photo?

The dolmen I ‘found’ today is an example. On Bruno Marc’s website it is listed as ‘Détruit‘ . That means it has been destroyed. Not Ruiné – his other classification – but gone.

Well – here is that destroyed dolmen I located today:

It’s small, but perfectly-formed : ‘un dolmen simple des causses’. There’s even a capstone, resting on the remains of the tumulus. It’s just one of the dozens that litter the sunny foothills of Les Montagnes Noires – the modest communal sepulchres of ‘les Pasteurs des Plateaux’.

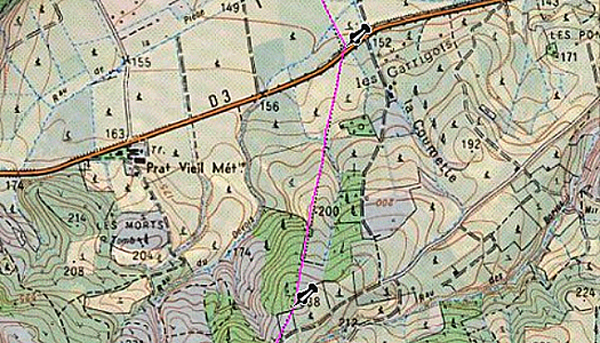

This is how I found it :

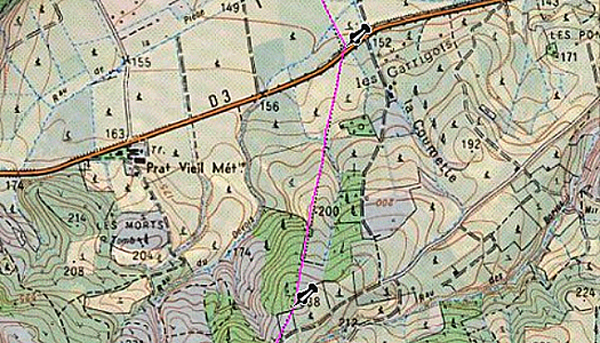

That’s a sketch-map of some of the dolmens Paul Ambert found in the early 1970’s. On the left are three dolmens that his team excavated : Combe Marie, Violon and Lignières (see their Pages). On the right was all I had to go by today – a handful of symbols scattered over a few hundred acres.

The terrain : room-sized islands of blindingly bright limestone rubble, encircled by thorny thickets of evergreen oak and spiney juniper. I employed the usual mix of GPS and GoogleEarth print-out :

And I worked my way through the scrub from point to point, making detours wherever a ‘tumulus’ of stones came into view. The little dolmen was nowhere near any of my expert guesses. I just stumbled across it.

And so these dolmens disappear off the map of ‘Prehistoric France’. According to Bruno Marc, it no longer exists. It was destined – until I turned up – to be yet another of the region’s lost and forgotten neolithic sites. There are many more to be ‘found’ again. The aim of this blog is to report my on-going research into the archived histories of these prehistoric sites – and to precisely locate them for posterity. It will involve, of necessity – the correction of inaccuracies and the deflation of fictions.

The record of this visit can be found on the permanent Pages. However, its precise GPS location and a full description will only be available through S.E.S.A.(la Societé des Etudes Scientifiques de l’Aude) in Carcassonne, prior to the publication of a book of my discoveries of the prehistoric sites of the Corbières and the Minervois.

When I walked into the big old schoolroom that houses the library of one of France’s oldest learnéd societies : ‘la Société des Etudes Scientifiques de l’Aude’ ( SESA, at Carcassonne ) a few years ago – my heart sank. But my spirits lifted.

Underfoot lay grey-brown splintery boards of a much-trodden lecture-room, while Languedoc sunlight was made to stand outside. A few dusty old men bantered amongst desks and shelves. I’d been expelled from a school like this, for being a troublesome misfit – but now those walls of books were a welcome sight. They held the information that would lead me to the megalithic sites that have gone unseen and unreported for half a century.

My boots and haversack caused a stir before I’d uttered a word. I was their first English member in a long while – and I was intent on hunting down every last one of their long-lost dolmens. I was their B-movie Harrison Ford – and all I needed were the clues. SESA has provided me with most of them.

But there is a body of knowledge that is never written down, that never reaches Carcassonne let alone Paris. The megalithic tomb they call simply ‘le Bac’ has been known to generations, around Rouffiac. This knowledge did not reach the ears of Marie Landriq – keen amateur historian of her region – until she was about to leave the area in 1924. She sent the discovery in, to La Société Préhistorique Francaise (SPF) at La Sorbonne – who merely accorded it a passing mention.

She calls it the dolmen de la Roudouniero, from the ‘townland’ where it is located.

That brief note of her discovery is the first of just three mentions of this large strange dolmen. There is no published report on it, and no photo – online or in any library. In the 1920’s Sicard notes that there is a third dolmen to the south of Paza, in his ‘Deuxieme Excursion dans les Hautes-Corbières’ . In the 1960’s Jean Guilaine has an annotation referring to a ‘dolmen Sud ou dolmen III de Paza’. In the 1990’s J-P Bocquenet, in his doctoral thesis, attempts to make a case for a necropolis at Paza, based on the hearsay of Sicard. It’s evident that he never visited the place : the three megaliths are scattered over too wide an area. In the 2000’s Bruno Marc – frequently declared as the expert on all things megalithic in Languedoc – seems completely ignorant of its existence. Or of any of the other megaliths around it. This is how knowledge degrades and disappears – just like old stones.

When Germain Sicard went exploring for dolmens and menhirs that summer in 1922, he knew he was going ‘out into the wilds’. Little seems to have changed in the century that separates our visits : it is still ‘Les Corbières Sauvages‘ to most of our comfortable contemporary historians. It’s just that Sicard went to great lengths – on bicycle and on foot – to visit these extraordinary prehistoric sites, and to report on their state – while our current ‘experts’ seem reluctant to put their boots on. Even to visit the library.

[More photos and information on La Roudounièro dolmen page, to the right.]

It’s July Friday 28th. 1922, the second day of Germain Sicard & Philippe Hélèna’s visit to Camps-sur-l’Agly. Germain is 71 and a founder-member of France’s oldest natural history society, SESA ( and twice its president), and young Philippe will soon inaugurate Narbonne’s Musée de Préhistoire. This afternoon Marie Landriq and her husband, Octave, the village school-teachers, plan to take them to see a ‘dolmen’ that they had discovered the year before, near the village, close to the top of a massive rock outcrop called le Roc d’en Mourges. Eighty-odd years later I am following in their footsteps – but it is not made easy : there is no Roc d’en Morgues on the map. It may be le Roc d’en Benoit. In old Languedocienne, both Mourges and Benoit signify a monk. I am not convinced that it is anything more than an accidental rock-formation.

Les Landriq found calcinated bones and blackish or blackened (noiratre) pottery shards close-by. This may well have served as a funerary site in some distant past – but its very situation on a steep slope, plus the absence of real orthostats, and the lack of any dateable grave-goods – all should have insisted to Sicard, that this was not a dolmen at all.

But these were early days for archaeology – and besides, Sicard was a guest of Les Landriq – and Marie Landriq may possibly have been ‘a formidable woman’ – such that the 71 year-old doctor found difficult to contradict. On the subject of questionable rock-carvings and ‘cupules‘ Sicard apparently has his critics: Yves Le Pestipon of L’Astrée website is one –

‘Rares sont ceux qui croient en Germain Sicard. Des archéologues bien connus le traitent d’affabulateur.’ [that he makes up stories . . .]

Yves is a prolific writer and researcher of dolmens and rock-carvings : here, he is bemoaning the fact that Sicard might have misled him concerning some ‘cupules’ in a rock. He finally finds them – and finishes by celebrating Sicard’s accuracy on this occasion- ‘Germain Sicard n’est pas un affabulateur !’

In the course of my travels in the wheel-ruts of Sicard and Co. this summer, my doubts about Marie Landriq’s finds have been replaced by admiration and amazement. Her zeal and dedication resulted in a handful of significant discoveries : her own Page will appear soon.

Les Landriq have a few more neolithic discoveries to show the experts from Carcassonne, and after a day of rest, it’s just Octave and Germain who mount their bicycles and head east through Cubières and Soulatge, to reach Ruffiac. On the way they pause at Paza where the owner of the domaine tells them blithely that he recently knocked down a dolmen at Coumezeil, a farm close-by. M. Guizard nous parle encore d’un autre dolmen, que lui-même aurait détruit récemment près de la bergerie de Counezeil, au nord de Paza, un peu à l’ouest de la côte 411.

Sicard did not go to examine it. This could possibly be the dolmen referred to in Michael Hoskins’ Corpus Mensurarum, as Paza 1. Nor is the picture clarified by J-P Bocquenet, who – in his doctoral thesis of 1994 (supervised by Jean Guilaine) – writes about La nécropole de Paza :

Trois dolmens et un petit site d’habitat constituent cette nécropole. Certains auteurs citent un cromlech qui serait en fait un dolmen ruiné ou un menhir. Les structures mégalithiques se trouvent sur la pente sud de la colline qui domine la bergerie de Paza.

This is confusing on a number of accounts: there is indeed a menhir in the vicinity – and it is most definitely not a ruined dolmen but stands within a distinct cromlech of stones : I visited it during this trip. It has recently been waymarked – by a local man, Jean-Jacques Pannolié, who is acknowledged as an expert in these matters – as a cromlech, and I have unearthed Mme. Landriq’s notification of it to the Société Préhistorique Francaise, in June 1924. My photos of it appear on the Coumezeil menhir and cromlech Page, to the right.

So it would appear that Boquenet was blindly citing other authors and did not visit any of these sites. There is no necropolis at or near Paza, or Coumezeil, for that matter. A necropolis must consist of more than two tombs – let’s say ‘within a stone’s-throw’ of eachother. The menhir and cromlech are about 800 metres from Paza, and 500 from Coumezeil. No one has yet provided any precise locations for Paza 1 dolmen, or II, or III. There is another menhir at Trébals, but that is 2.5 km. from Paza. And there is another dolmen, at La Roudouniero (found by Marie Landriq a year later : Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 1923). It stands 900 m. south of Paza – yet has been called Paza III.

Let us leave the confusion at Paza behind – as did our pair of dolmen-hunters. They have another 8 kilometers on their ‘machines’ ‘ under the fierce rays of the sun, along stoney roads – before they reach la métairie de Triolles – or Trillol as my map has it. They leave their ‘bécanes’ there and set off on foot for the last climb, with their knapsacks of ‘vittals’. The 71-year-old Germain must by now have been feeling his age, for he settles down in some shade while Octave disappears into the undergrowth.

Sooner, probably, than he wanted he gets a call – and it’s off again up the slope. A short scramble later Sicard finds himself ‘en face d’un beau dolmen, bien entier, qui se dresse majestueusement . . .’

And it is a surprise, and a remarkable sight, after all the sad little ruined and degraded tombs scattered over the hills of les Corbières and le Minervois. It’s a complete and rather impressive ‘dolmen simple’.

It is worthy of inclusion in any guide-book, but it does not appear in any report or guidebook, or on any map. How regional historians have missed this – is yet again beyond my comprehension. A local team have done good work in clearing and waymarking the track – but have not yet alerted the wider public to this impressive megalith.

Sicard quickly realises that it has been ransacked – and has a culprit ready to hand : ‘l’agent-voyer, qui surveillait l’exécution de la route de Montgaillard, M. Isidore Gabelle, collectionneur érudit et acharné’.

It was, he suspects (and with absolutely no proof) the Superintendant of Roads, who is a learnéd and voracious collector. But they get over this bitter moment and decide that, given the beating sun, they should enjoy the shade offered by the dolmen – and have their picnic there, under its table.

I too settled in, set out my solitary snack, and thought of them. Trois hommes dans un dolmen (sans parler du chien).

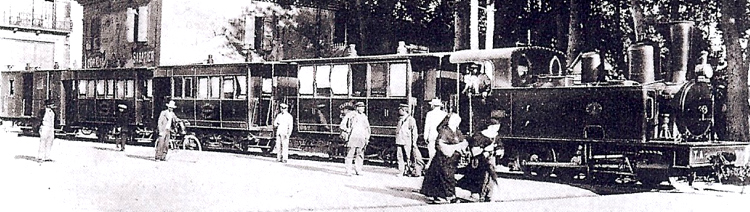

It was a fine end to Sicard’s second visit – but there was a long bicycle ride ahead. For Octave it was the 20 km. ride home to Camps – but for Sicard it was 30 kms. down through Les Gorges de Galamus to the station at St. Paul-de-Fenouillet, and the long journey back to Carcassonne.

Germain Sicard – doctor, wine estate owner, speleologue and archaeologist – has been an amiable companion throughout this summer. His first journey into ‘Les Corbières Sauvages’ was blighted by an easter blizzard, with no dolmens explored and little to report.

A second invitation was offered by ‘notre dévouée collègue Madame Landriq’, who had meanwhile discovered some ‘nouvelles instances’ – more dolmens for the 71 year-old enthusiast to explore. So on July 27th. 1922, he secured his bicycle in the guard’s van at Carcassonne station – ‘d’aller de nouveau dans cette si intéressante, si sauvage et si peu explorée région des Corbiéres.’

At 9.20 two trains pulled in to the station at St. Paul de Fenouillet – his and the train from Rivesaltes bringing the 22 year-old Philippe Héléna – ‘tous grands amateurs de préhistoire’. Then it was off on their ‘bécanes’ up the 12 kms. through the Gorges de Galamus to Cubières-sur-Cinoble, where they met M. and Mme. Landriq, and enjoyed ‘un excellent repas champêtre’.

The four then set off on their ‘machines’ up the road to Soulatge. The dolmen de l’Arco dal Pech is now marked on the IGN Serie Bleu map and is part of a walking trail – back then it was a steep trackless scramble up through trees and box-brush to the summit. Did Mme Landriq wear long skirts – or was she modern enough to sport cycling knickerbockers (‘rationals’)?

[ She will get a Page to herself, in due course – Les Dolmens Imaginaires de Mme. Landriq.]

It’s a stiff thirty minute walk up to the one, two or three dolmens above Cubiéres, and Sicard was not disappointed with the massive, but rather dislocated megalithic tomb at the top.

He and I were less impressed with the other two ‘dolmens’ thirty metres down the slope.

It looks to me more like a diaclase – a wide fissure in the bedrock. I have seen and read about diaclases used as tombs – particularly up at the nécropole de Bois Bas. They may have been used as sepulchres in times of population-stress, when the tribe’s numbers were being severely reduced through epidemics (living close to animals was convenient – but deadly to a group that had not developed any immunities.)

Les Landriq had, so they said, found a quantity of grave-goods at or ‘near’ all three ‘dolmens’. Germain Sicard was not about to pour cold water on their enthusiasm that day. His account, if read carefully, does allow room for conjecture.

The team that are responsible for the waymarked track to the l’Arco dal Pech dolmen at Cubiéres, must also have read Sicard’s ‘Deuxième Excursion’ and have cleared around the two other graves. But essentially it is ‘Le beau dolmen bien conservé’ that Sicard came to see, that merits its own Page – where more information and photos will be posted.

Meanwhile the four of them carried on to Camps, where they spent the night at the Schoolhouse. This visit we set up our tent at La Ferme at Camps, where we met an international crew – some of whom have been loyal to the place for 27 years.

This was just the start of a busy weekend of megalith-hunting for Germain and me. I consider myself fairly fit – but I was having trouble keeping up with his itinerary. The following morning Sicard set of at first light to reach a barely known ridge that he called ‘le plateau de Moufri’ (this might be one of his typos, and thus should be Monfri, which might relate to the ridge called Frigoula) high above les Gorges de Galamus. This promontary is largely unknown : it is variously called ‘Frigoula’ and ‘Les Remparts des Sarrazins’. This was Mme Landriq’s next surprise.She thought it might be a Bronze-age defensive settlement, and subsequent researchers have confirmed her findings.

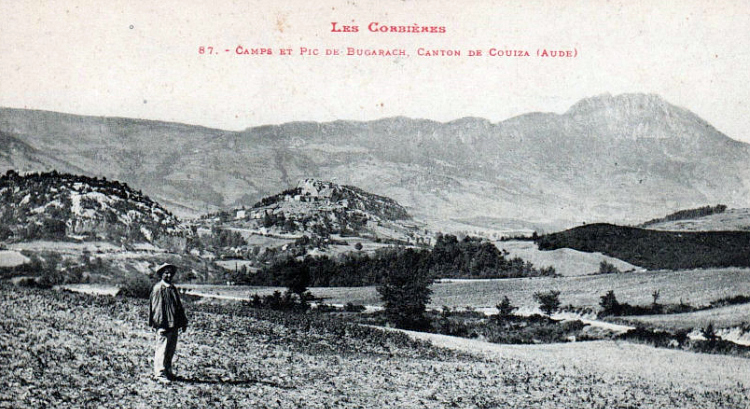

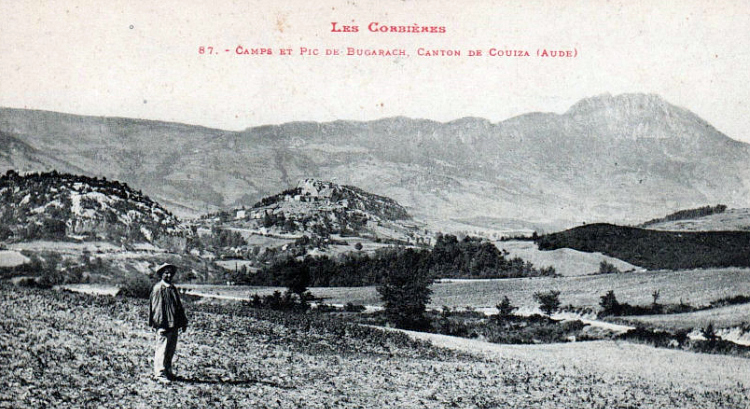

I had set myself the task of following Germain and Philippe, step by step out of the village, as the sun rose. The landscape no longer looks like this, with cleared fields and man and animal persuing hard but productive work.

The story of Camps, and how it was almost abandoned, and how it was bought by one man, and how it was allowed to return to wilderness? Well – that’s all for another story in another blog.

The walk to the ‘enceinte fortifiée’ of les Remparts des Sarrazins is detailed on its own Page, to the right.

The glorious late July weather allowed me to enjoy a ‘déjeuner sur l’herbe’ as did Germain and Philippe and Les Landriq, not to mention the miller from le moulin de l’Agly who led them high up onto the giddying peaks above Les Gorges.

It’s impossible to show how many hundreds of metres above the Gorges this is. The video replays some of the alarm I felt. This is an extreme defensive position, replicated throughout the region, where Bronze Age tribes felt threatend by invasive forces – and it was probably not long held or needed. It feels very much like the hillfort above our village of Moux – random vestiges of a temporary position constructed rapidly in time of extreme fear and uncertainty.

Again : more info and photos on les Remparts des Sarrazins Page.

As I settled to my lunch, having descended from one of the more extreme places of the Bronze-Age peoples – I realised that Sicard was above all else, a writer. He collected people and experiences and he shared them. Another Natural Scientist might have fussed about the stones under his feet – but Germain, at ease upon his back having descended from this alarming place of safety, could recall these thoughts :

Mais il faut quitter ce merveilleux spectacle, et redescendre les sentiers que nous avons trouvés si ardus à la montée. Nous déjeunons dans la vallée de Riol, près de la source, et pendant que nous reposons mollement sur la pelouse, deux aéroplanes passent bruyamment sur nos têtes, faisant vibrer l’air de leurs ronflements sonores, et filant dans l’azur comme des vautours.Ainsi après avoir visité sur le plateau de Moufri les débuts de la civilisation, nous envoyons franchissant l’espace la merveilleuse évolution.

One small aeroplane passed overhead as I descended. I had fervently hoped that some jet or other piece of machinery would so time its arrival to allow me to mirror and echo and double Sicard’s experience. It did – and I recognised it as a tourist plane taking photos of what is now the bigger show in town : the ‘Cathar Castles’ – for which this region (for better or for worse) is now so well-known.

[NB This post is being copied in its entirety over on to the Page section: Sicard’s 2nd. Excursion.]

There is a Page on the Cubières dolmen or l’Arco dal Pech – to the right.

In 1922, Monsieur Germain Sicard made three Excursions into Les Hautes Corbières, at the invitation of Madame Landriq, schoolmistress at Camps-sur-l’Agly, who had found a number of dolmens in the region. She and her husband were regular correspondents to La Société des Etudes Scientifiques de l’Aude, S.E.S.A. at Carcassonne, and had begun a collection of prehistoric artifacts.

The journey down – by train and tramway, omnibus and jalopy, bicycle and foot – was arduous and exhausting. Les Tramways à Vapeur de l’Aude, running on thin rails and an uneven roadbed, were noisy and noisome. The roads, largely unmetalled, were either stoney or muddy. Lodgings were infrequent, sanitation rudimentary, electricity unheard-of.

Germain Sicard – in company with, variously: Antoine Fages, Philippe Héléna and les Landriq – came three times to this ‘si intéressante, si sauvage et si peu explorée région des Corbiéres.’

Sicard was a founder-member of SESA in 1889 and by 1923 had been twice elected President. He was 71 when he wheeled his ‘bécane’ into the end wagon at Carcassonne train station and headed south in search of dolmens.

This summer I wedged my bike into the back of the car – amongst Mary’s plein air impedimenta: easel and stool, boards and paints and rags and brushes – and set off to follow in his tracks. These prehistoric burial sites have never been marked on any map: they were in danger then of being lost – and are now again in danger of being forgotten. Two years back I set myself the task of not letting this happen: I didn’t realise it would open up a world of friendships and fantastic places.

[Sicard’s accounts of his three Excursions dans les Hautes Corbières, with my contemporary findings, can be found under ‘Sicard’s Excursions’ in the Pages side-bar – where there is much concerning trams and travel, food and friendship, and naturally all kinds of old stones.

The dolmens and menhirs he and I explored – they all come under their own names with their own pages:

Cubières dolmen, Trébals menhir, Trillols dolmen, Paza menhir and circle, La Roudounièro dolmen (or Paza III), Les Remparts des Sarrazis hillfort.]

Nous sommes en plein cagnard. It’s scorching now from 10 to 6 – so any excursions on days off must happen at dawn or not at all. I don’t need an alarm in the summer here – most days start around sunrise. So it’s off at first light across the valley to the pretty little hameau de Fauzan in search of the second dolmen de Fournes that eluded my Jessi and me the first time, and me a few weeks ago.

Like most men, I’m reluctant to ask directions – seeing it as a defeat of my navigational prowess. But I have also discovered that good fortune comes from talking to people out on the hillside – and so it was that my daughter and I found ourselves being conducted to Fournes dolmen No. 2 by a cheery vigneron, after a fruitless afternoon thrashing through the garrigue. She was back in France again – but fast asleep – when I set out to recover some of my honour by finding No. 1, tout seul.

Paul Ambert’s 1970’s report on the two Fournes dolmens states confidently that ‘on peut facilement les trouver’. Well, it’s always easy when you know how – but more difficult when the only two references to them contradict eachother. Ambert gives a fairly precise description of No. 1’s location – while managing to mix up the latitudes & longitudes – as 500 m. to the east of Fournes. Michel Barbaza’s 1979 ‘Inventaire de l’Aude Préhistorique’ echoes this, but puts No.2 at 100 m. to the south-west, when it is in fact 750 m. to the south-east. But the confusion was compounded by the hand-drawn sketch-map, possibly borrowed from a 1946 dig by le Docteur Arnal :

This looked so useful at the outset – but in fact led to hours of vain searches : the lower dolmen (No. 2) was nowhere near this position, and nowhere near a track. Another description of the southern dolmen as having been a shelter for children on the way to school must have been a garbled mis-literation of some local story : it’s several hundred metres from the track between the two hamlets. The conflicting locations, the confused story and the inaccurate map all succeeded in scrambling my understanding of where these two dolmens were in relation to eachother – or to anything else.

The description above – ces deux ruines – coupled with the humble-looking sketch-plan, left me feeling that maybe there wasn’t much remaining of tomb No. 1, and that I would probably never find it in the invasive garrigue:

In fact, it turned out to be quite sizeable and solid – once the undergrowth was cleared back:

It really was buried in the thickest of thickets – and I’d be amazed if more than one or two people know of its existence, or its location. What a shame that it has been so long ignored : its position is dramatic and the uneroded stones are massive and have great presence.

More photos & info & video on the Fournes dolmen 1 Page >