Manufacturing Consent

part one:

part two:

[The text in brackets was excluded from the video due to time constraints.]

As the economic crises deepens people have begun to question some of their preconceptions about capitalism. But people have questioned capitalism before. What keeps people from radically challenging our economic order? Why do we consent to the rule of capital? Why do we consent to our own exploitation? This video seeks to offer some insights into the origin of this consent.

Like any other economic order capitalism is a system of social relations- social relations between people as they produce things in order to meet their needs and desires. In a capitalist society these relations take the form of market exchanges- of commodities which are exchanged for money. Thus we often get the impression that money or commodities are in the driver’s seat… that money is what rules the world, or that commodities have value and social influence by themselves. And it is true that through money and commodities we express value and social power, but this value and this social power comes from somewhere else- from the basic social relations that lie behind market exchange: the social relations between people as they produce things.

This should be the starting point for any truly radical social theory. If we understand that economic orders are not magical, that they aren’t endowed with mystical powers or god-given impermanence, but that economies are social relations of our own creation… if we understand that then we have already taken the first step toward figuring out how to change the world.

But this is precisely the opposite of the way we experience capitalism. We experience capitalism in atomized form: each of us an isolated individual wondering through a world of blind, impersonal market forces that act upon us. Though we may not like the state of affairs in the world we don’t engage in actions to change them. Our freedom to act upon the world and change it is restricted to the realm of market freedoms: the freedom to choose which commodities to buy and which capitalist to sell our labor (labor power to be specific) to. We don’t have the freedom to not choose these things: We can’t not buy commodities or not sell our labor to a capitalist (1). We can choose the specific content of our market interaction but we cannot choose the form itself. The commodity is the basic form for the way we exchange the products of labor and wage-labor is the basic form by which workers enter production. This is the limit of bourgeois freedoms. We can choose the specific content of our consuming and producing but we can’t change the basic forms. [ We are free to consume and free to sell our selves but we are not free to challenge the basic form of markets and private property that lay behind this world of bourgeois freedom.]

[This world of bourgeois freedom is an enticing world. In a world which is devoted to producing more and more attractive commodities, the freedom to buy things can seem like the horizon of human freedom. The power of such arguments are easily seen in current attacks upon proposals for a single-payer health-care system. It is claimed that a single-payer system will take away our ability to make choices in the market place. The collective freedom to create a more humane and affordable health care system with equal access for all is demonized as an assault upon the most sacrosanct of bourgeois freedoms: the freedom to consume. Of course, there is nothing about a single payer system that would actually limit one’s choice of doctors, but just evoking the specter of an attack on consumer freedom is enough to elicit powerful, emotional responses from Americans.]

Libertarians bask in the glory of bourgeois freedom. For them bourgeois freedom serves to end all discussion of the social relations of capitalism. If I choose to go to work, the libertarian argument goes, then I am consenting to wage labor, which somehow legitimates capitalism relative to all other economic systems. Thus their argument becomes, “Capitalism exists because people choose it in their market interactions.” But this is circular reasoning: market interactions can only express capitalist outcomes. You can’t choose a non-capitalist world through the market. Effecting some sort of anti-capitalist movement requires actions that go beyond these bourgeois freedoms, actions that transcend the market behavior of isolated individuals. It should be no surprise then that whenever we see workers organizing to form a union, or community groups organizing to control development libertarians complain that these collective projects for collective freedoms are distorting the market and attacking our essential freedoms as individuals.

We are free to sing Lee Greenwood songs and make vague speeches about freedom all day long. But as soon as we question the market or private property we come up against the coercive arm of the state. Our vast legal and prison systems and the extensive imperial overreach of the capitalist military form a powerful defense around the sacrosanct private property of the capitalist class. We are free to challenge a lot of things in the capitalist world, but private property forms the border around those freedoms. The state will spare no violence in defense of private property.

Every social order has a limit, a horizon beyond which things cannot be questioned. And this limit is usually enforced by some sort of violent, coercive arm. Feudal Europe had a class of knights that ensured the obedience of the peasant classes. A capitalist society has a state with its legal system, police and military to protect private property, impose order upon markets and maintain the integrity of the currency. Yet this coercive nature is clearly not enough to help us understand the question at hand. No matter how much theory may expose the exploitative basis of wage labor or the brutal realities of capitalist development we must face the fact that most of us freely consent to our lot as wage laborers- that our everyday lives do not compel us forward toward some final confrontation with capital, but instead acclimate us to not think out of the box, to not question the social order. Often, the longer we work the more habituated we become to wage-labor. Why is this? Why do we consent to our own exploitation?

Many people often try answer this question by discussing the way ideology is imposed upon us. The basic idea in such arguments is that through the airwaves, televisions, schools and newspapers we are being inundated with brain-washing propaganda designed to make us happy-workers, devoted consumers, and mindless drones. It is not hard to come to such conclusions when we look at the sheer volume of advertising we absorb daily, all devoted to this cause. It is not hard to see how the structure of capitalist media ownership selects media in a way that reinforces its own view of the world.

As helpful as this view of ideology may be, it is not the whole picture. It makes ideology look like it is something entirely imposed from above. It makes consent look like something stamped onto unthinking, unintelligent lemmings. The reality is that consent and ideology spring out of the basic structure of the market itself and that they would exist with or without televisions, billboards or schools.

We have already seen how the basic structure of the market, free exchange between formally equal individuals, creates the appearance of freedom and equality. [It was from the emergence of markets that our modern notions of freedom and equality come from. In the marketplace all that matters is price. It does matter who you are buying from, whether they be Kings or peasants, black or white.] This world of market freedom and equality masks a world of coercion and inequality in the sphere of property and production. After all, why does a worker need to enter the market place to purchase their means of subsistence? Because they do not have the ability to produce it themselves. Why does a worker enter the market to sell her working life to the capitalist class? Because she does not own any means of producing commodities herself. Thus the very fact that a worker enters the market to buy commodities and sell wage-labor implies that there is an asymmetry in the ownership of production. But we don’t see this in the marketplace. All we see is formally equal people exchanging commodities. Nobody is forcing anyone to buy or sell anything. Thus market exchange itself obscures the coercive asymmetry behind the market.

The market obscures the source of profit as well. Though workers create more value than their wages the capitalist doesn’t receive this value until these commodities are sold in the market. At the end of the working day the worker leaves with a wage and the capitalist leaves with a bundle of commodities worth more than their initial investment. But these commodities must be turned into money in order for the capitalist to complete this process. In the market anything could happen. If workers in competing firms have produced the commodity more cheaply our capitalist will have to sell his commodities under their value. If our capitalist has a monopoly on production he will be able to sell his commodity above its value. Thus the market appears as the source of profit. The creation of surplus value in production, through exploiting workers, is hidden from view. Of course these market prices are the result of the total social productivity of labor, but we can’t see the total social productivity of labor. All we see is market prices. And so the market itself, the act of exchange itself, appears to create value.

Bourgeois economic theory mirrors this world of appearances perfectly. It sees profit emerging from the process of exchange itself. It ignores the wider social relations of production. It ignores the way the total social productivity of labor effects market prices and market behavior. It treats the isolated, free act of exchange in the market as the only interaction worth analyzing. It then deduces that all economic phenomena must be able to be explained through that isolated interaction, without recourse to any wider picture of social relations.

This is the way ideology really works. It is not imposed from above. It grows naturally out of the basic structure of this world of appearances. We don’t even need newspapers, or televisions or schools to brainwash us into obeying the social order. We develop these ideas freely through our daily journeys through this world of appearance.

There is a contradiction between the world of appearance and the social relations behind it: We live in a world of freedom in which none of us are free; A world of formal equality filled with barbaric inequalities. This is not just some illusion imposed upon reality from some conspiratorial elite on high. The coercive and unequal social relations of capitalism can only be expressed through the freedoms of the marketplace. The social antagonisms of capitalism can only be experienced as bourgeois freedom.

Part two:

Workers leave the workplace at the end of the day with enough money to buy their means of subsistence. This means that over the course of their working day they have created enough value to reproduce themselves. Thus the working class reproduces itself each day.

At the end of the day the capitalist finds him/herself holding a wad of profit. This profit comes to him/her merely because he/she owns capital, not because they have created any value. It is the surplus labor of the working class which produces the capitalist’s profit. Thus the worker reproduces the capitalist and capital each day as well.

And this is the true and ugly nature of capitalist alienation. It’s not just that we are dominated by blind, impersonal market forces that we cannot control. It’s that that blind, impersonal world of capital is something that we produce and continue to produce everyday. The workplace is the site of our own domination of ourselves, a domination we reproduce every time we punch in and begin our work. Yet we don’t see this as the result of social relations between people in the workplace. Instead the powers of capital seem to spring from the market itself.

Moreover, this market appears as the realm of individual freedom. It appears to be just isolated individuals making free and equal, fleeting exchanges- free from any wider social relation. From this world of bourgeois freedom springs a conception of the world which becomes our ideology- an ideology where freedom means buying and selling things, and where the individual’s right to buy and consume is sacrosanct. Rather than being externally imposed, this ideology grows out of the very core of the market itself.

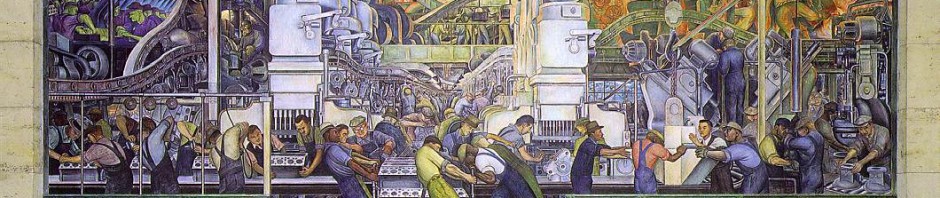

This focus on the market takes our gaze away from the workplace where the domination of capital is less obscured. The workplace is clearly a meeting between the propertied and the propertyless. A worker doesn’t exercise unrestrained freedom in the workplace. His labor belongs to the capitalist who may use it anyway he chooses, and he chooses to use it in the most productive way possible. So why then is the workplace not more of a site of all-out class war. Surely we have a long history of militant labor activity in the capitalist world. But we also have a long history of consent: consent to the domination of capital over labor in the workplace. So we must ask, “How is this consent manufactured?”

The manufacture of consent in the workplace is very similar to the way we saw consent produced in the marketplace. Behind any relation of power must ultimately lie a coercive and possibly violent power. The capitalist class owns the means of production and has a vast legal apparatus to back up its claim to the fruits of the working class. But in addition to this coercive threat of violence exists a world of appearance generated by the phenomenon of choice.

We saw that in the market our freedom lay in our ability to choose between different types of commodities to buy and different capitalists to sell ourselves to. We are free to choose the specific content of our consuming and working, but we are not free to choose our way out of the form of commodity exchange or wage-labor. We saw that this is a choice over content, not form.

In the workplace we also see domination masked by a world of appearance- appearances generated by this same logic of choice. If the factory was a site of total domination of the worker, if scientific managers like Frederick Taylor had really gotten their way and created workplaces of total domination, the antagonisms of capitalism would be much more apparent and we would probably have a much more radical working class. But workers always maintain some degree of autonomy in the workplace. The choices they make as they navigate their way through the working day create a world of apparent freedoms that mask the social relations behind them.

Marxist sociologist and writer Michael Burawoy saw this very thing when he worked in a machine shop in the 1970’s. Burawoy noticed that the workers in his shop didn’t direct their energy toward resisting exploitation. Instead they turned their work into a game- a game they played all day, everyday trying to maximize their pay and beat the system. Burawoy’s shop was a piece-rate shop (2) which meant that the men were paid more if they produced above quota. Of course if the men produced too much over quota the quota was raised. So there was a game to trying to produce as much as possible in order to maximize pay, while not producing so much that the quota was raised.

The game was made interesting because workers were given different jobs each day. Each day was a challenge to try to get the best job from the man who handed out jobs, argue with that man about what was the right quota, get the right parts from the guys who gave out parts, follow the instructions right, make the machines work, etc. A worker’s day was entirely consumed with trying to navigate the complex hierarchies among workers, master the machines, pace one’s work just right, etc. They called it “making out”. When Burawoy met other workers in the shop the question was always, “Are you making out?” which meant, “Are you beating the quota?”

In a world of deprivation or domination, relative satisfactions can be quite compelling. In a world in which we are deprived of our ownership over our own labor we must occupy ourselves with lesser pleasures. In Burawoy’s machine shop it was this constant battle to beat quota that gave workers a sense of purpose and excitement throughout the day. It transformed a boring, repetitive job into one in which workers could exercise creativity, skill and a sense of relative autonomy. These small freedoms created a world of appearance in which the real antagonism between labor and capital was transposed into a complex, shifting social hierarchy

among workers and a fight against the machines.

And doesn’t this happen whenever we play a game? When we play a game we must consent to the rules of the game. When we play chess we don’t question why a pawn can’t move backward. If we did we would never win the game.

When we work we play a game. It may not be a game to “make out” under a piece-rate system, but it is a game to survive yet another working day, to make out as best we can, against all the obstacles we may confront. We all have our strategies. We all have a secret formula we try to follow to make it through each day. This world of autonomy that we carve for ourselves is the way we survive the workday. But in playing this game we focus on relative satisfaction. The game becomes an end in itself. We begin to think of work as a place where individuals exercise freedoms in their attempt to maximize their own personal satisfaction, not a place where one class dominates another.

Even in the realm of labor struggles the logic of the game continues. Unions play a game to grow the union and this game implies consent to the rules of the game. If unions were to ever threaten the end of capital they would also threaten themselves. How can we have a union without a capitalist? Once established, unions often become the method by which individual worker grievances are addressed or by which individual workers are punished for breaking the rules. The concept of a collective assault upon capital becomes replaced by the concept of the union as a regulator of class-relations. The union becomes the equivalent of an “internal state” which regulates the capital-labor relationship, reducing it to a matter of individual grievances, redirecting collective power into the concerns of individuals, keeping tensions from disrupting work, and guarding the status-quo of the rules of the game.

This logic of the game, of relative satisfaction from a narrow range of choices, extends to much of our life in a capitalist society. When we comparison shop for the most affordable apartment to rent we forget that the landlord-tenant relationship is purely exploitative. When we engage in electoral politics we allow two nearly-identical political parties to define the political spectrum. This is one of the trickiest things about bourgeois society. We all have no choice but to navigate our way through a capitalist world trying to do the best we can. But as we do so we create a wold of appearances, appearances that distort and hide all of the class relations around us.

The 21st century presents many opportunities for the left, but there is also a lot of theoretical work to be done. As we comb through the long history of the 20th century, examining the failures and successes of the left we should be paying attention to what games were being played, what tacit rules were being obeyed. The labor movement, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the feminist movement…. how were their successes limited by the limits of the game?

And as we think about the creation of future movements how do we confront the enormity and power of bourgeois ideology, an ideology that grows organically out of the basic structure of markets and work. Where are the cracks in this ideology and how do we best exploit those cracks?

Footnotes

(1) Of course there is the Libertarian argument that workers do have the choice not to sell their labor to a capitalist, that is that workers can save money and become self-employed if they choose. Let us look a little closer at this argument. At one level it is just another version of the claim that because all market actors enjoy formal equality in the market (by formal equality we mean that nobody can force anyone else to buy or sell anything- that we are free to buy and sell from whomever we like) that all market decisions imply total consent with no coercion, and that this defines the ultimate horizon of human freedom. etc. As I point out in the video, this mistakes content over form. We have the choice over the content of our wage-labor but not over the form of wage labor. The only working activity in a capitalist society that does not fit into the wage-labor relation is that of the self-employed person. Marxists probably haven’t spent enough time exploding all of the ideology and mythology that grows out of the self-employment idea. Firstly, become self-employed and surviving at it is not easy. For one, there are a relatively small number of occupations that one can choose. Any job that generates a significantly large income will attract the flow of capital, which will flow into the market and dominate it with wage labor. A self-employed person will find it hard to compete against wage labor. A capitalist firm can produce things more cheaply due to the cooperation of many workers and the deployment of labor-saving machinery. A capitalist firm can even deflate prices, a la Starbucks or Wallmart, in order to force smaller competitors out of the market. But there are still all sorts of niches that are available to the self-employed, niches that resist the domination of big capital. In order to start a business people often have to take out loans from a bank or rent property. This means that part of the surplus they produce goes to the capitalist class. That is, instead of working directly for a capitalist who owns means of production, they have to rent or lease the means of production from the capitalist class and thus still end up giving surplus value to the capitalist class. The self-employed person, the small business owner with 1-2 employees, they often act as little more than low-level managers for money-capitalists or landlords. On the grand scheme of things, they do very little to actually escape the circuit of capital.

(2) In a piece rate system instead of being paid an hourly wage workers are paid for the amount of commodities they make. While at first this may appear less exploitative, Marx actually argued that piece-wage were “the form of wages most appropriate to the capitalist mode of production.” (Das Kapital, Marx, Penguin edition 1990, p. 698) Though workers are paid for each product they create, they are never paid the full value of the product they create. If this happened there could be no profit for the capitalist. Instead, workers are given a quota of products they must create and they are paid per product at an average rate. If they work faster than the average rate, creating more commodities, they are paid an extra amount. Thus the worker has an incentive to work faster and for longer hours in order to make more money. But the faster they work the more surplus value they also create for the capitalist. Thus piece rate system becomes a sinister tool for roping the worker into participating in his own exploitation. Today we see elements of the piece-rate system in all sorts of work, especially in telemarketing and sales.

In Burawoy’s shop workers typically averaged 125%-140% above quota. If too many workers worked too high above quota the company would raise the quotas on the workers. So workers had an unwritten agreement among themselves not to work at more than 140% above quota. Workers who worked above 140% were called “rate busters” and they became the object of extremely hostile social pressure from other workers. So as to not be a good-for-nothing rate-buster, workers who were having an easy time “making out” might save a little of their work on the side as a “kitty”. That is, they would produce more than 140% but they would not turn it all in to the boss at once. They would save a little on the side as a kitty so that they would not have to work as hard later. This became a big part of the game: working really hard to save up a kitty and then sitting back and taking it easy later.

Suggested Readings:

“Manufacturing Consent” by Michael Burawoy.

In this book Burawoy explores many of the ideas in this video, analyzing from first hand experience the way in which the labor process generates its own consent. His ideas are powerful. I highly recommend this book. Many people may notice that the title of this book is the same as one written by Noam Chomsky and Ed Herman. Their book is about the way ideology is constructed in the media. While a good book on many fronts, it fails to identify the way the experience of capitalism itself generates a lived-experience, a world of appearance that generates its own ideology all by itself.

Essays in Marx’s Theory of Value by I.I. Rubin

This is one of the best books on Marx’s economic theory that I have ever read. It has great explanations of the fetishism of commodities which is what a lot of part 1 of the this video is based on.

Das Kapital Vol. 1- Karl Marx

See chapter one, the section on fetishism of commodities.

Hi,

I like it – says it as it is (pity the dialogue is spoilt by the intrusive music)

For the end of capitalism and a sane society.

David Jennings

Hey Brendan, is it alright if I upload a version of your video with spanish subtitles to my youtube channel? of course crediting your autorship.

Patricio