Happy Birthday King James I!!

Happy Birthday King James! James I of England, whose birthday is this Sunday, June 19, is the “King James” of the King James Bible. He became King James VI of Scotland at the age of one in 1567, after his mother, Mary (Queen of Scots) was forced to abdicate. Mary was implicated in the death of her second husband (and cousin), Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, James’s father. As retold in novels, plays, opera, and films, Mary herself was imprisoned, and eventually beheaded, by her cousin (once removed), Elizabeth I of England. When Elizabeth died in 1603, James inherited her throne. One weirdness in this succession is that James inherited the crown from the queen who executed his mother, but since Mary was likely involved in the murder of his father, he probably had mixed feelings about her death.

When James came down from Scotland, his new English subjects were naturally concerned about their new king’s religious views and the future of church organization and worship in England. To settle matters, James convened a conference in January of 1604 at the palace of Hampton Court. Though it was not on the agenda, the project for a new translation of the Bible originated in these discussions.

Despite popular misconceptions, James himself had little to do with the translation, apart from setting it in motion,and providing it with royal sanction. (The translators prominently dedicated it to him, too.) He was a learned monarch, deeply engaged with theological questions, and he wrote a number of metrical versions of Psalms. But his learning was not up to the level of the translators.

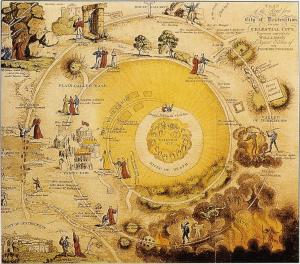

His one area of contribution to the translation was in shaping the guiding principles for the translators (written by Archbishop Richard Bancroft), especially in the decision to avoid marginal interpretative notes. Such notes had been a popular feature of the Geneva Bible, but a number of these, written by Protestant exiles during the reign of Queen Mary, were sharply critical of monarchs. The King James Bible, as it came to be known, was to be free of such a radical taint. Little did James know that the Bible he sponsored would become the Bible of the radicals John Milton, John Bunyan (author of Pilgrim’s Progress, right), and William Blake, as well as of America, the British colonies that threw off their king to become a democratic republic.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

This entry was posted on June 18, 2011 by Hannibal Hamlin. It was filed under From the Curators, Influences, The KJB in History and was tagged with American colonies, Authorized King James Version, birthday, Elizabeth I, England, Folger Shakespeare Library, Geneva Bible, Hampton Court, John Bunyan, John Milton, King James Bible, King James I, Mary I, Mary Queen of Scots, Scotland, William Blake.

Leave a comment