Sommer wins Lasker for vitamin A discovery

By KAREN ZABEL

BALTIMORE – For only the second time, an ophthalmologist has been lauded by the half century-old Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation.

Alfred Sommer, MD, dean of the School of Hygiene and Public Health and professor of ophthalmology, epidemiology, and international health at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, received the 1997 Albert Lasker Clinical Research Award for his work studying vitamin A deficiency in children with xerophthalmia. The foundation annually honors clinicians involved in pure medical research, and seeks to educate the public on the importance of medical research. The last ophthalmologist honored by the foundation was the man who nominated Dr. Sommer-Arnall Patz, MD.A foundation spokesperson said that 65 of the approximately 340 Lasker recipients have gone on to win a Nobel prize in their field.

Alfred Sommer, MD, dean of the School of Hygiene and Public Health and professor of ophthalmology, epidemiology, and international health at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, received the 1997 Albert Lasker Clinical Research Award for his work studying vitamin A deficiency in children with xerophthalmia. The foundation annually honors clinicians involved in pure medical research, and seeks to educate the public on the importance of medical research. The last ophthalmologist honored by the foundation was the man who nominated Dr. Sommer-Arnall Patz, MD.A foundation spokesperson said that 65 of the approximately 340 Lasker recipients have gone on to win a Nobel prize in their field.

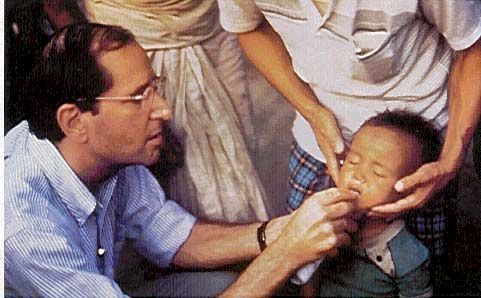

According to the foundation, Dr. Sommer, 55, received the award and its accompanying $25,000 for “the understanding and demonstration that low dose vitamin A supplementation in millions of Third World children can prevent” blindness and death from infectious diseases.

Although Dr. Sommer’s initial work involved administering supplemental doses of vitamin A to thousands of Indonesian children with varying degrees of xerophthalmia and chronicling the natural course of the disease, the research gained new meaning and a far broader scope as links with measles and childhood mortality rates became apparent.

A new perspective

Dr. Sommer’s first exposure to Third World medicine came in the mid-1960s with a trip to the then-infant nation of Bangladesh. Working with colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control, the doctor joined a team of researchers studying cholera in that country. Although his international work with xerophthalmia was still a decade away, Dr. Sommer said the experience forever altered his philosophy and perception of the role of medicine.

Asked to assess the needs of the country’s population after a cyclone, during a period of civil unrest, and again during a smallpox epidemic, Dr. Sommer began to consider health questions in terms of entire populations, rather than single patients.

“I began to think of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people,” he said. “From then on, my orientation was different. I was always looking at bigger issues as far as research was concerned. It gave me a population perspective.

“That’s also where I became very interested in epidemiology and public health,” he recalled.

After returning to the United States, Dr. Sommer decided to pursue a master’s degree in epidemiology at The Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health before completing his ophthalmology residency at Wilmer.

“My guiding philosophy has always been, ‘Chance favors a prepared mind,’ which is a quote from Louis Pasteur. My own complement to that: ‘If a research project turns out as expected, you haven’t learned anything.’

“Whatever contributions I have made have largely been something other than what I started out looking for, as is the case with many contributions in science,” he said.

“Basically, there are lots of important issues and lots of hints that come your way. I have had that opportunity many times, that when you are concentrating on an issue in a broad perspective, some clue comes along, a hook that gives you a unique insight that you wouldn’t otherwise have had,” he continued.

Chance indeed favored Dr. Sommer in 1976 when, hoping for an opportunity to return to work abroad, he was asked to initiate a study of xerophthalmia in Indonesia. Severe forms of the disease were associated with high levels of mortality, which was attributed to the fact that these children, near blindness, also had more serious, life-threatening diseases.

Dr. Sommer designed a comprehensive battery of questions, a sort of “everything you need to know” regarding vitamin A deficiency and blindness.

For 3 years, Dr. Sommer and his co-workers administered vitamin A supplements to 4,600 Indonesian children every other month, to examine the effects of the vitamin on xerophthahnia, and to determine the clinical pathogenesis of the disease and the most practical means of treating it.

Diet and other lifestyle habits were recorded to explore why some children became vitamin A-deficient and others did not.

A surprising revelation

Two years later, Dr. Sommer found himself back in Baltimore, compiling data that had not yet been analyzed, when Louis Pasteur’s specter once more tapped him on the shoulder. Although the study had set out to determine the effects of vitamin A deficiency on xerophthalmia and to examine the distribution of the disease, a surprising revelation was about to occur, one that would dramatically alter the course of the research’s conclusions.

Two years later, Dr. Sommer found himself back in Baltimore, compiling data that had not yet been analyzed, when Louis Pasteur’s specter once more tapped him on the shoulder. Although the study had set out to determine the effects of vitamin A deficiency on xerophthalmia and to examine the distribution of the disease, a surprising revelation was about to occur, one that would dramatically alter the course of the research’s conclusions.

“One of the important issues that had not yet been analyzed was why some children became vitamin A deficient and others didn’t. As I was reviewing the data, it became apparent to me that something was occurring that I had not anticipated,” Dr. Sommer recalls. “And as I thought about it, I realized that what was happening was that children who were vitamin A deficient were in fact dying at a much higher rate. It was a real, ‘Holy cow!’ kind of experience for me.

“It was really quite striking, because not only was there an association between even mild xerophthalmia and increased mortality, but the more vitamin A-deficient the patient was, the higher the mortality rate became. It was truly a dose-response relationship, which is the kind of thing that makes an epidemiologist like me feel warm and fuzzy. You begin to realize that maybe this is not just a random event, but may well be causal,” he said.

“At the same time, we were in the process of starting a large clinical study in which 20,000 children were randomly assigned to get vitamin A or not, to see if this would prevent xeropthalmia. To this study, we added the data on childhood illness and death rates’ “

When the study was completed 3 years later, the results were much the same: children who received the supplements every 6 months had a 35% to 50% lower death rate than those not given the vitamin.

Skepticism ensues

Although the data were published in The Lancet and accompanied by a supportive editorial, the results met with much skepticism from the medical community

“Nobody was willing to accept that two cents worth of vitamin A was going to reduce childhood mortality by a third or half, let alone when that information was coming from an ophthalmologist,” he recalled. “A lot of people had spent their lives studying the complex amalgam of elements leading to childhood deaths, and here we are suggesting that we can cut right through this complex, causal web and give two cents worth of vitamin A and prevent those deaths. It didn’t sit well.”

Undaunted, Dr. Sommer and supportive colleagues continued to repeat similar studies in other countries.

The results were the same.

“All the trials came out the same, which was really quite to my amazement, given all the different cultures and environments in which the trials were done. Yet, all the studies had a 35% to 55% reduction in childhood mortality, whether you gave the capsule once every 6 months, every 4 months, or every week, or if you put a little vitamin A into something they ate once a day,” he said. “It all came out essentially the same, which was quite heartening.”

As these larger xerophthalmia studies were taking place, Dr. Sommer turned his attention to another important cause of childhood blindness in Third World nations.

“Measles is far and away the most common cause of childhood blindness in Africa particularly, and also happens to be associated with a very high mortality rate. I hypothesized, could some of this be operating through the vitamin A mechanism? Could measles be causing an acute decompensation in the vitamin A status?” he recalled.

The answers were waiting for him in a small hospital in Tanzania. Here, children hospitalized because of severe measles were given large doses of vitamin A on two successive days.

The results? A 50% reduction in the mortality rate of the treated children.

With such unmistakable data in hand, wheels began to turn. UNICEF issued a recommendation that all children with measles receive vitamin A as part of their treatment. In 1993, the World Bank declared vitamin A supplementation to be the single most cost-effective intervention anywhere. And last year, UNICEF’s annual report highlighted vitamin A supplementationas a classic example of how much can be done with so little.

The New York Times’ 1997 Christmas Day edition featured an editorial about vitamin A deficiency, and cited Dr. Sommer’s current work with vitamin A treatment of women of childbearing age, treatment that has reduced maternal mortality rates by 50%.

How does it work? According to Dr. Sommer, one of the key roles of vitamin A appears to be in maintaining the body’s resistance to infection, particularly through an enhanced immune response.

“Presumably, what we are seeing is that we are not preventing children from getting an infection, but the severity of those infections is much attenuated and less likely to lead to serious illness and death,” he said.

Dr. Sommer will travel to Holland in June to receive the Duke-Elder Gold Medal for contributions in international ophthalmology, an award presented every 4 years by the International Council on Ophthalmology.

And he continues to be involved in research overseas, including work in fostering more affordable cataract surgical techniques in developing countries and his study examining the effects of vitamin A on the mortality rates of pregnant women.

“Next fall, I will have the opportunity to go back to the field for 3 months, to help start up a new, large study in vitamin A and maternal mortality and morbidity, and to develop ophthalmic resources in southeast Asia,” he said. “That’s something I can’t do too frequently, given my administrative responsibilities. But I will enjoy every minute of it.”

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

“Reproduced with permission from Ophthalmology Times, Vol. 23, No. 4, Feb. 15, 1998 issue (pages 1, 40, 41, & 53). Copyright by Advanstar Communications Inc. Advanstar Communications Inc. retains all rights to this article. This article may only be viewed. User may not actively save any text or graphics/photos to local hard drives or print pages to paper or duplicate this article in whole or in part, in any medium. Advanstar Communications Inc. home page is located at http://www.advanstar.com.“