The Easterlin Paradox is a socio-economic effect, coined by Richard Easterlin in 1971, which refers to the theory that relative levels of money have much more influence on our psychological wellbeing than absolute levels. The theory was proposed after Easterlin noticed that people’s happiness, while higher for affluent people within countries, was not higher between countries. That is, a person earning $100,000 per year in America would report being happier than his $40,000 compatriot, but would be no happier than a Hungarian earning $40,000 per year. It is in our ability to compare ourselves that our sense of wellbeing lies, not in how much money we actually have. Easterlin equally proposed a non-linear trajectory on a happiness vs money scale. Past a certain point of basic need provision (shelter, food, security), he suggested that continued economic growth does not substantially influence our expression of happiness. As Carol Graham, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, said: “happiness seems to rise with income up to a point, but not beyond it.”

The strength of Easterlin’s case came from readily available data that indicated that,

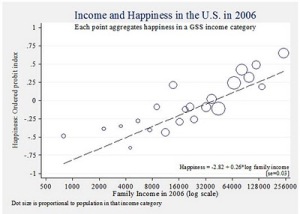

Easterlin’s original graph of happiness vs income

despite an unprecedented rise in economic strength and purchasing power, self-reported happiness in the USA and the UK had plateaued in 1950, and had even started decreasing in some populations during the 1970s.

At the time, his theory was championed by the hippy movement. Once we have our basic needs for survival, that extra $10,000, that new flatscreen, that electric bottle-opener is not really going to make us happier. Importantly, other studies showed that while that extra $10,000 doesn’t make a huge positive effect on your happiness, losing the same amount was a significant blow to one’s wellbeing. Loss aversion is a well-documented phenomenon in human psychology, and so reduction in pay or retrenchment has negative affect consequences significantly out of proportion with the actual loss.

Easterlin’s paradox became the theoretical base underlying an alternative economic paradigm where government’s role was to promote stability rather than growth. This way, people would not be so exposed to job loss with its concomitant negative consequences, while theoretically the slower growth would not have a significant dampening effect on people’s happiness. In recent years, given the impending disruption of anthropomorphic climate change, not to mention the widespread discontent caused by the follies of the financial crisis, Easterlin’s theory is again attracting new champions.

However, in 2008, two economist, Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson, challenged the validity of the paradox, stating that their “findings indicate a clear role for absolute income and a more limited role for relative income comparisons in determining happiness”. They built upon work earlier in the decade by Veenhoven and Hagerty who came to a similar conclusion. It seems as though Easterlin’s ideas, perhaps relevant 40 years ago, are not so applicable now. We are left with the question: does the Easterlin paradox bear up under scrutiny, or not?

This post is not designed to answer that question. I think that Easterlin’s ideas resonate with a lot of people who are disillusioned with the current state of economic affluence. However, in weighing up the arguments and counter-arguments, I think it’s important to note several points. None of these points are game-changers, but I think worth considering when we get into the misty realm of ‘happiness economics’.

Firstly, as a philosopher friend of mine’s elegant thesis concluded, happiness and welfare are vexingly difficult to measure. Self-report is fraught with cultural, sexual, social obstacles that distort responses. This contributes to ongoing debate about the accuracy of the data. Moreover, happiness is influenced by relativity (how happy we were yesterday affects our mood today) and habituation (a heightened mood induced by a positive event slowly loses its lustre, and generally returns to a person’s base level of happiness). Any government that tries to succeed in ‘happiness economics’ is bound to be challenged by these shifting affects.

Secondly, relativity itself is relative. The argument that Wolfers and Stevenson bring is that the effects of absolute income are a powerful predictor of happiness. That is to say, a person earning $200,000 per year in Australia will be happier than someone earning $100,000 in Hungary, even if they exist on relatively similar socio-economic levels within their countries. However, I wonder whether the growth of the mass-media and the Internet have negated any sense of proximal versus distal relativity. Our Hungarian can measure himself just as easily against our Australian as against his fellow countrymen, because of the spread of information and programming across the planet. This globalisation creates an environment that highlights rather than downplays relative income disparities.

Thirdly, affluence is a pretty good deal. Economic growth can pay for investments in scientific research that lead to longer, healthier lives. It can allow trips to see relatives not seen in years or places never visited. When you’re richer, you can decide to work less — and spend more time with your friends. It is churlish not to recognize the benefits of the west’s current economic strength.

The Easterlin Paradox is attractive because it can stand as an empirical basis for that reassuring trope: “Money can’t buy you happiness”. But someone might do well to remind Easterlin that, as Groucho Marx once said, “it sure makes misery easier to live with”.

Hi LT Carpo,

Great post… as always. I’m really fascinated by the what contributes to well-being (or lack there of).

Take the following example:

“…Respondents were asked to rate their happiness on a 5 point scale. Some of them had won between $50,000 and $1million in state lotteries within the last year. Others had become paraplegic of quadriplegic as the result of accidents. Not surprisingly, the lottery winners were happier than those who had become paralyzed. What is surprising though, is that lottery winners were no happier than people in general. And what is even more surprising is that accident victims, while somewhat less happy than people in general, still judged themselves to be happy'”

Barry Schwartz, in his book The Paradox of Choice, outlines two well established causes of “hedonic adaption”, or the tendency of people to adjust their psychological disposition to the circumstances around them. ‘First, people just get used to good or bad fortune. Second the new standard of what’s a good experience (winning the lottery) may make many of the ordinary pleasures of daily life (the smell of freshly brewed coffee, the new blooms and refreshing breezes of a lovely spring day) rather tame by comparison”.

The idea of hedonic adaption might explain the constant drive for new experiences, which in the modern economy, often means consumerist behaviour. As people consume, they experience pleasure – “as long as the things they consume are novel. But as people adapt, as the novelty wears off, pleasure becomes replaced by comfort. It’s a thrill to drive a new car for the first few weeks, but after that, it’s just comfortable… the result of having pleasure turn into comfort is disappointment, and the disappointment will be especially severe when the goods we are consuming are ‘durable’ goods, such as cars, houses… And as society’s affluence grows, consumption shifts increasingly to expensive durable goods, with the result that disappointment grows.”

By now, if you are someone who chases new experiences through purchases, you’re really in trouble. You just chase faster and faster for new experiences, seeking out new “commodities and experiences”, but get nowhere. You are on the “hedonic treadmill”, and adaptation is partly to blame – you just keep becoming accustomed to the new things or experiences you acquire. Worse still, even if you do manage to raise your number of average “hedons” (i.e. average happiness level) a secondary trend has been observed in which people simply become accustomed to the higher level of happiness, so that what feels like +20 happiness today soon becomes set as your default position. So to be happy, you need to begin striving for more happiness once again.

Given the apparent inability of the human mind to accurately remember its experiences, perhaps if we want to be happy we should follow the lead of Voltaire’s character Candide. After experiencing unimaginable horrors from one end of the world to the other, Candide notes: “we must cultivate our garden”. I think Candid is suggesting that by setting to work, some of the key problems of happiness above discussed are rendered redundant, and may even be resolved.

Really interesting post. Great to get such clear info on the paradox. In particular, the analysis of why it might be complex. The point about welfare is great, and also how globalization complicates inter-country studies. People say that the Arab revolutions had elements of this – the ability to see what other political systems and ways of life were possible.

It’s really interesting how Wolfers and Betsey updated Easterlin’s ideas. Science and data are so important in shaping ideas about society and the individual, but science itself develops and changes over time. Its nice to remember this process, as it can help us avoid theoretical dogmatism. This post seems to do that – to draw attention to interesting ideas and note their complexity, rather than offer a final answer.

Puwl I also really like the idea of cultivating one’s garden!

Hey guys I was on a train the other day, thinking about Polyology and this post, and thought about a possible connection between the hedonic treadmill and something from evolutionary theory called the ‘Red Queen’s Hypothesis’:

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass the Red Queen describes a race where “it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place”. In evolutionary theory this is taken to represent how a species must continue to adapt and evolve in their environment simply to maintain current levels of relative fitness.

More info: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Queen's_Hypothesis

Do you think there’s some connection here with the hedonic treadmill? A hint at why it might be that we continually seek progress/growth/development/’more’? Haha I don’t want that to sound fatalistic though!

Pingback: Does Economic Change Make Us Less Happy? « Theories and Concepts

Pingback: 2011 in review | Polyblog