Beaverton-based Vernier Science Education has provided tools for science classrooms since 1981. Now the company is transitioning to a perpetual purpose trust so it can maintain its commitment to serving teachers — and has hired a new CEO to lead the way.

It started out with what Dave Vernier describes as “a few little computer programs.”

The programs were written to help students do things like make graphs, or to simulate things kids couldn’t easily do in the real world, like launch satellites or study projectile motion.

“Apple IIs got pretty popular in schools,” says Vernier, who was then working as a physics teacher in Hillsboro. “When I got started writing programs for them, I saw right away that they really helped me in my teaching. Then I said, ‘Well, there are a lot of other people that have these, and maybe we could try start selling them.”

His wife, Christine, who had worked as a social worker and the manager of a law firm, took out an ad. It was supposed to just be a summer gig for Dave — but the software sold.

Hardware followed.

The Verniers learned how to build photogates — timing devices that measure times of the changes in state of an infrared beam, making for extremely accurate timing of physics experiments. They can be used for studying free fall, air-track collisions and the speed of a rolling object, and they have in recent decades become a staple in physics labs.

“We just would tell people how to build these photogates, and eventually people said, ‘I don’t want to build them, you build them,” Christine Vernier tells Oregon Business. “So we got into the hardware thing. But we really never did plan to; for a long time, it was just going to be a part-time job.”

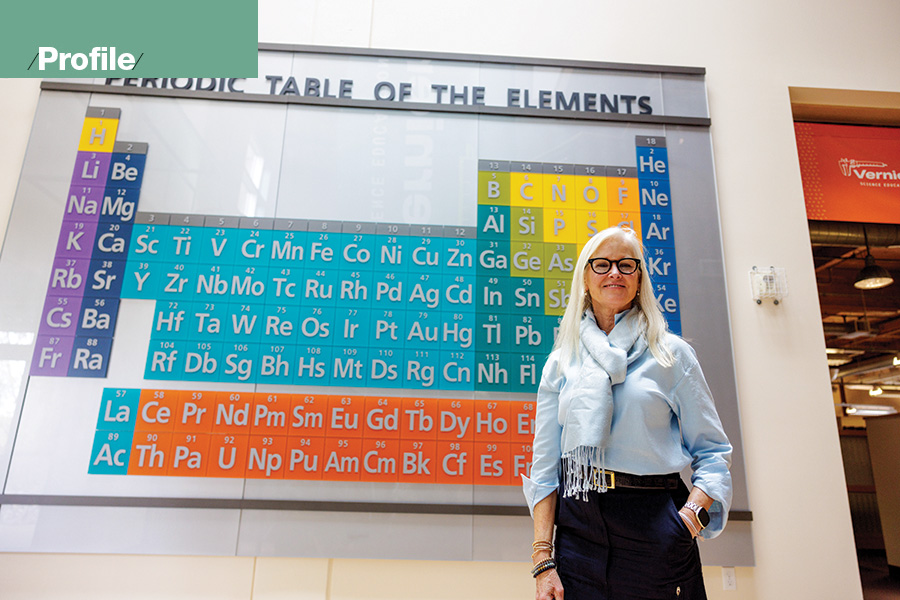

Vernier Science Education incorporated in 1981, with Dave as CEO. He served in that role until 2015, when John Wheeler took over. Now Jill Hedrick has taken the reins at the Beaverton-based company. A veteran of the educational tech industry and the daughter of a teacher herself, Hedrick says the company is continuing its emphasis on working directly with teachers to make sure Vernier’s products meet their needs.

Part of that is recognizing the ways in which the education field is changing, she says. In recent years, in part due to COVID, a large number of educators have retired or left the field to do other things, which means there’s a large new cohort of teachers coming to the classroom who are newly certified. And many, she notes, have gone through “nontraditional paths to becoming a teacher.”

“One of the things that we are always thinking about — because it is our charter — is this legacy of service to educators. If groups of educators are shifting, we need to understand how we continue to serve newer teachers and having a higher percentage of new teachers in each school environment than we may have seen historically,” says Hedrick. “That’s been a fascinating way of just thinking about what we need to do in order to continue to be a trusted partner.”

Vernier announced Hedrick’s hiring in March. Hedrick’s résumé includes executive positions at Northwest Evaluation Association, which creates academic assessments for K-12 students, and Turnitin, which makes a plagiarism-detection tool, as well as roles at other technology companies.

“My dad was a teacher and a principal and an administrator, and later taught at the university level, so it was something that impacted me from the very earliest age — the idea of education being the great equalizer, the value and importance of education, and really understanding the experience of a teacher, and an administrator, having lived with one,” Hedrick says. “So it felt very natural for me to be having conversations with educators and school district administrators — and a couple of the companies that I’ve been a part of also served higher ed. It very much comes from the heart.”

According to the Verniers, Hedrick was one of three finalists for the position, found after a nationwide search. They weren’t expecting to recruit from Oregon but found the right fit in Hedrick, who has lived in the Portland area since 2010.

“Jill really stood out as somebody who got it — who understood our mission, who was passionate about it, who was passionate about people and our culture,” says Dave Vernier, who has continued to serve as co-president of the company since stepping down from the CEO role.

Since its founding, Vernier’s product line has expanded to include temperature probes, sensors, lab equipment and spectrometers, primarily used in K-12 science classrooms. Customers are very often science teachers making purchases with their own classroom purchasing budgets, though they may also be principals or district-level administrators making purchases, Hedrick says.

“The other thing is, Jill has experience with selling to school districts,” Dave adds. “And that’s critically important, as in the past, we’ve marketed mostly directly to teachers. We would impress some particular physics teacher in the old days, and maybe when they got a budget for the year, they’d buy some stuff from us. It was strictly teacher to teacher, but now that the world is changing, so much more of the sales of things to education is done on a district-wide basis, and she’ll have some experience with that.”

Hedrick steps in as the company transitions to a perpetual purpose trust — a model that transfers stock ownership to a trust, with the stipulation that funds be used to maintain a specific mission. Dave says the board decided to shift to a perpetual trust model after exploring various models for a succession plan when Wheeler announced his retirement. The perpetual purpose trust model — also recently adopted by the outdoor-gear company Patagonia — was appealing because it meant the company’s commitment to education would never change, Dave says, and that the company’s culture and structure could remain intact.

“In establishing the trust, you set up these objectives, and so our objectives are things like — of course — be financially stable, but also take care of our customers, take care of our employees, give back to the community, be sustainable, environmentally sustainable, have the best tech support in the industry” Dave tells OB. “All those sorts of things that we do now are all laid out in writing, and the company has to report to a trust board every year, saying, ‘OK, what have you done to meet all these objectives?’ The whole formality of it gave us assurance that the company could continue the way it is, and that it would act the same way, which was reassuring to us and to the other partners.”

“They’re one of these businesses that does a lot beyond just selling their products,” says Erika Shugart, CEO of the National Science Teaching Association, a professional association with 35,000 members. She notes that the National Academy of Science’s 2012 Framework for Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards that followed it both place a much heavier emphasis on hands-on learning than prior educational standards — the type of education Vernier’s products were created for.

“They were really ahead of the game there and have been well positioned to help support educators in their classrooms,” Shugart tells OB, adding that the company is a frequent exhibitor at its national conference and sponsors memberships that give teachers a discount when they join the organization.

The company, which currently employs 118 people, frequently appears on OB’s annual 100 Best Companies to Work For and 100 Best Green Workplace lists, and Hedrick says part of the draw of working for the company was the opportunity to continue philanthropic partnerships with organizations like the Oregon Zoo and the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry.

“For me, my passion around it really comes from this idea that we can do good for education through the use of technology, because it enables a personalization of an educational experience that we haven’t always had,” Hedrick says. “It’s a slow transition. But it’s also a really, really important one.”

Click here to subscribe to Oregon Business.