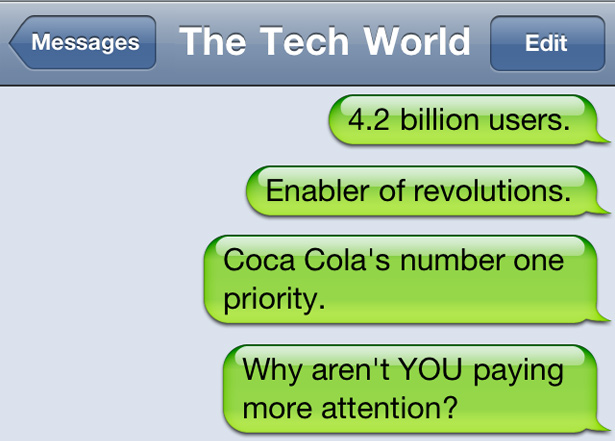

Why Texting Is the Most Important Information Service in the World

SMS dominates Internet usage in the developing countries where most of the world lives. Simple messaging is the driving force behind technology-enabled changes in commerce, crime, political participation, and governing.

The "feature" mobile phone is the globe's top selling consumer electronics product. For many of the world's poor, due to meager connectivity in rural areas and the costs of more advanced mobiles, these phones effectively support only voice and text (or SMS) functions. Feature mobiles have spread into some of the most remote areas of the globe, with 48 million people now with cell phones but no electricity, and by next year, 1.7 billion with cell phones but no bank account, according to one estimate.

Skyrocketing phone subscriptions in the developing world account for over 70 percent of total subscriptions. In May, Coca-Cola's Director of International Media, Gavin Mehrotra, announced that "SMS is [our] number one priority" in mobile marketing. A mobile analyst called it "a true bombshell announcement" that shocked the large marketing conference at which it was made. "The world's undisputed number one advertising brand, Coca Cola, says categorically, SMS is priority number one," the pundit wrote. "Wow."

Coca-Cola's big bet on SMS is revealing: for vast populations, SMS is the first readily accessible data channel, suitable not only for advertising but for governance, banking, and many other services.

For example, in the Philippines, jokes are circulated by SMS. In one, a local tour guide shows a foreign tourist the sights:

Pinoy Tourist Guide: This is cockfighting, our no. 1 sport

Tourist: Isn't it revolting?

Guide: No sir, that's our no. 2 sport

The joke has a remarkable basis. In 2001, citizens forwarded instructions by SMS to meet in protest, and the Filipino President Joseph Estrada was overthrown in what he later called a "coup de text." Today, the Philippines is often called "the texting capital of the world."

Hoping perhaps to turn SMS from a threat into an asset, Estrada's successor, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, whose nine-year Presidency ended in 2010, set up an abundance of creative SMS-based government services. She had political ads texted to voters. She set up a citizen complaint "line" with her initials: TXTGMA. She opened SMS-based services to report on crime, illegal drug activity, and pollution-belching government vehicles.

By 2008, the Philippines was providing SMS-based services from 54 national government agencies. And it seems to be working. According to one survey, 87 percent of Filipinos prefer communicating with the government via SMS, compared to 11 percent with an Internet-preference.

This isn't only a Filipino story. Governments in Kenya, South Africa, and Indonesia have launched similar services, some of which are remarkably creative. In Malaysia, flood warnings are sent by text via automatic water-level sensors. In India, citizens can check their application status for various certificates by SMS, shouldering out bribe-seeking middlemen. New and surprising programs seem to be launching all the time.

As Tony Dwi Susanto and Robert Goodwin, two experts on SMS-government, pointed out in 2010, "Current SMS-based [electronic]-government services can deliver most of the typical Internet-based e-government services."

Meanwhile, as documented in the 2009 collection SMS Uprising, efforts by threatened governments to control the spread of information by text have also multiplied in tandem with the technology. In Afghanistan, for instance, citizens can SMS directly to Twitter, but in Cameroon, the service was recently banned by the Biya regime in the wake of the Arab spring. Elsewhere in Africa, governments have had SMS services shut down completely in times of crisis.

Afghanistan provides a lively example of the potential of another SMS-based service to reduce corruption: mobile banking. While in the West, online banking is mostly a matter of convenience, the potential of mobile banking--in countries where it can reach sufficient scale--to increase transparency across the Global South could prove far more meaningful.

In 2009, NATO worked with the Afghan government on a pilot program in the Jalrez district to deliver the Afghan National Police Force's salary by mobile phone. Previously, cash was paid out to "trusted agents," who would then, after skimming, disperse the money. Under the new system, using registered SIM cards--which double as unique account numbers-- the policemen collect their entire salaries at a local cellphone office.

As Colonel Trent Edwards of the U.S. Air Force told the New York Times last year, the first time they were paid their salaries by phone, "the policemen thought they had gotten a 36 percent raise. They had no idea how much they were really paid."

One frustrated Afghan commander was so upset at losing his "share" that he commandeered his officers' SIM cards, took them to the cellphone office himself, and attempted to retrieve their salaries. Cutting down on such embezzlement by higher-ups is significant. While local Taliban pay recruits roughly $200 a month, low-level police are officially paid roughly $240. By eliminating the graft, the extra money may help reduce defections.

The Afghan National Police also discovered that at least 10 percent of salary payments had been going to policeman who didn't exist at all--another way that "trusted agents" collected extra cash. After moving to electronic delivery, similar numbers of ghost recipients have been found throughout the Global South across all cash-based "government to person" payments, a dismaying statistic that suggests just how much mobile and other electronic payments may help save developing-world governments. (Not all mobile money services use SMS technology, with USSD being another important data channel on low-end feature mobiles).

Beyond government and financial services, SMS is also being used to transmit and exchange agricultural, commercial, health, and educational information. In Uganda, a service called Farmer's Friend provides access to a special SMS database tailored to local needs. In partnership with the Grameen Foundation, Google sent out "Community Knowledge" workers to show residents how to use the service.

In one illustrative anecdote (reported last year by Phillip Kurata) a Ugandan woman was able to cure her ailing goat with help from one of the community workers. By texting "goat bloat" to the SMS database, the worker soon relayed the response: have the goat drink rock salt dissolved in water. Farmer's Friend is part of a suite of SMS-based services that includes the promising Google Trader, an SMS-based commercial marketplace.

Nokia's "Ovi Life Tools" offer agricultural, educational, and health information via SMS in India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and China. Txteagle, a business began by MIT's Nathan Eagle, now uses SMS surveys to perform research into emerging markets, paying for completed surveys in mobile airtime. In time, the impact of such services on local economies could be tremendous.

With mobile money, the possibilities multiply. Are there services that help list and sell products via SMS? You bet. Pay taxes by SMS? Yup. Buy clean water at mobile-payment vending machines? Sure. How about having a crop insurance payout sent directly to mobiles based on automated rainfall measurements? That's been done, too.

Last year, 4.16 billion users made SMS the most popular data channel in the world. An estimated 6.1 trillion texts were sent, up from 1.8 trillion in 2007. And while the proportion of customers using SMS for more than simple messaging is still small, in poor nations these services are already changing the nature of commerce, crime, reporting news, political participation, and governing.

Eventually, it seems, smartphones will drop in price, the necessary telecom infrastructure will expand and increase mobile Internet access, and feature phones will disappear from the global marketplace. For now, however, SMS services hold a world of untapped potential, transforming the text function into far more than a simple spinoff of the mobile phone.

Image: Alexis Madrigal.